Rodrigo Vergara

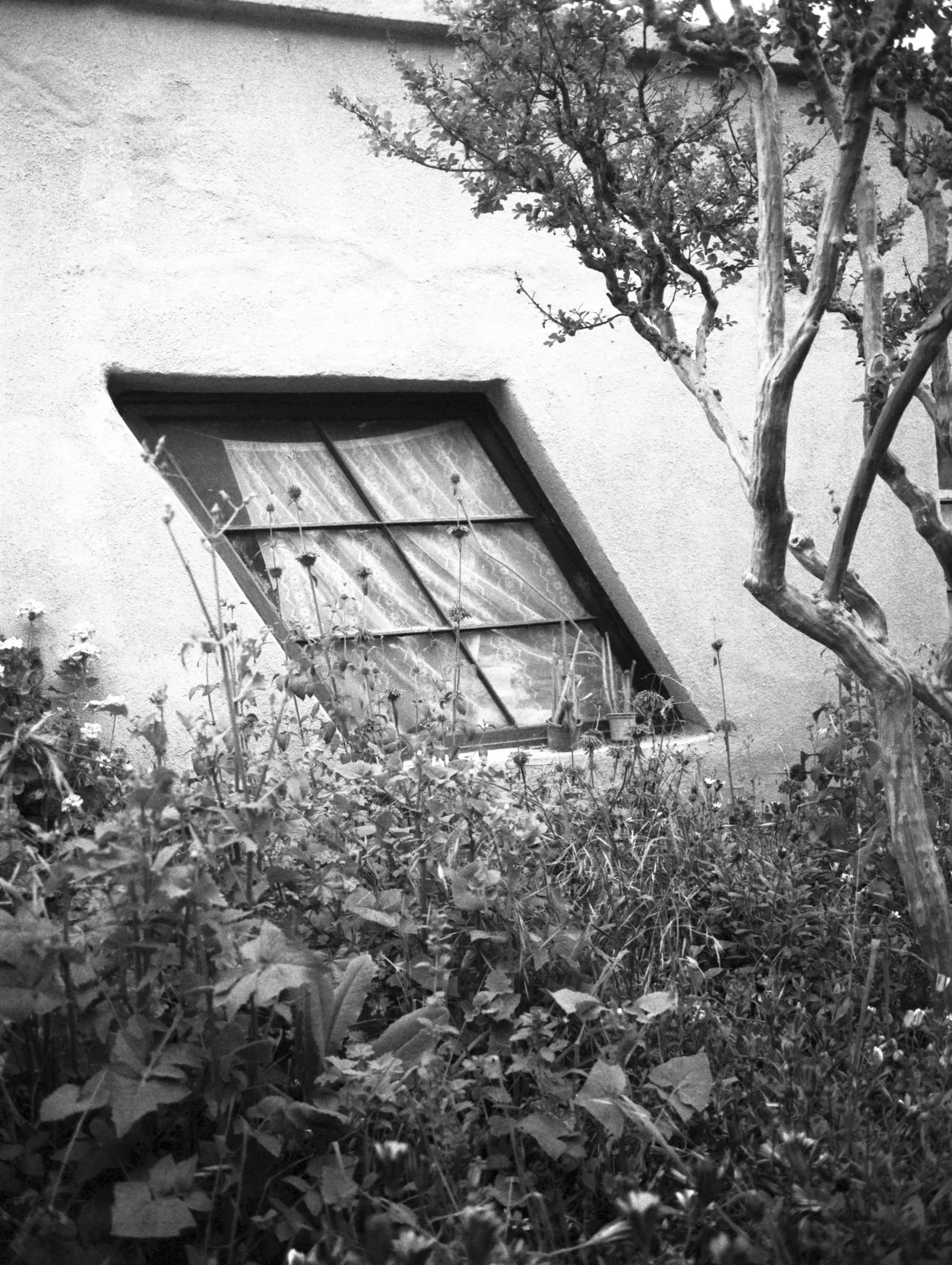

In the ash-soaked images of Chilean filmmaker and photographer Rodrigo Vergara, a critical substance emerges from latent states. Collisions and ruptures permeate seams of reality – doors, roofs, even the hide of a horse, become canonical figures. What is absurd gains a leverage of permanence. Within Pablo Neruda’s ‘Suddenly, A Ballad’ from Memoirs from the Black Island, a novel entity emerges from an ash bed, coercing a sacred effect: “Something is born in the depths of this, that was once ash, and the cup trembles with red wine.” One begins to believe that Vergara assumes such a role, observing in excelsis the consequential and once interrupted acts of mankind and its greater earthly mother.

The following images are born from sites across Chilé – Pucón, Santiago, Illapel – November 2021-May 2025.

“There’s a small fracture in things that makes them real—like spotting a typo in a text, a kind of bump that pricks us, like a needle forgotten in the bed. My work emerges from something close to that error, a capture of the unexpected. We live in a world full of human decisions that the internet can’t grasp, and that’s where I focus my energy: on everyday surfaces, moving through cities and the abandoned towns of Latin America, marveling at the ways we invent to solve our problems—the creativity of my neighbors, the rage that makes us want to burn it all down, the latency of a life being lived, of a past that exists and that we can mold, to shape images like clay.

And isn’t it fun to play with clay? Though we have to be careful—when you mix the colors too much, all you’re left with is a dull gray mass, stripped of character.” – Rodrigo Vergara

“The photograph of the burned bench is significant because the building behind it is the Instituto Nacional, one of the oldest high schools in Chile, where both Presidents and revolutionaries have studied. Young people demonstrate there every week against the injustices of this country.”

PAPANIKOLOPOULOS: How has your photographic work extended to your film projects? What remains, what dissolves... how do you counter and reinforce both mediums?

VERGARA: Working as an electrician in film has allowed me to travel through Chile. I’ve been to places I never thought I’d know, from towns steeped in history to truly beautiful and inhospitable landscapes. Talking with people and creating ephemeral bonds with their environment—something like an explorer sketching his journeys—has been a driving force in my search for images, and it is in this way that my work has been forged, naturally. I like to collect small stories and share them with those close to me: legends of people who have never known anything beyond their village in the middle of the driest desert in the world, or abandoned buildings in the midst of a town of 150 people.

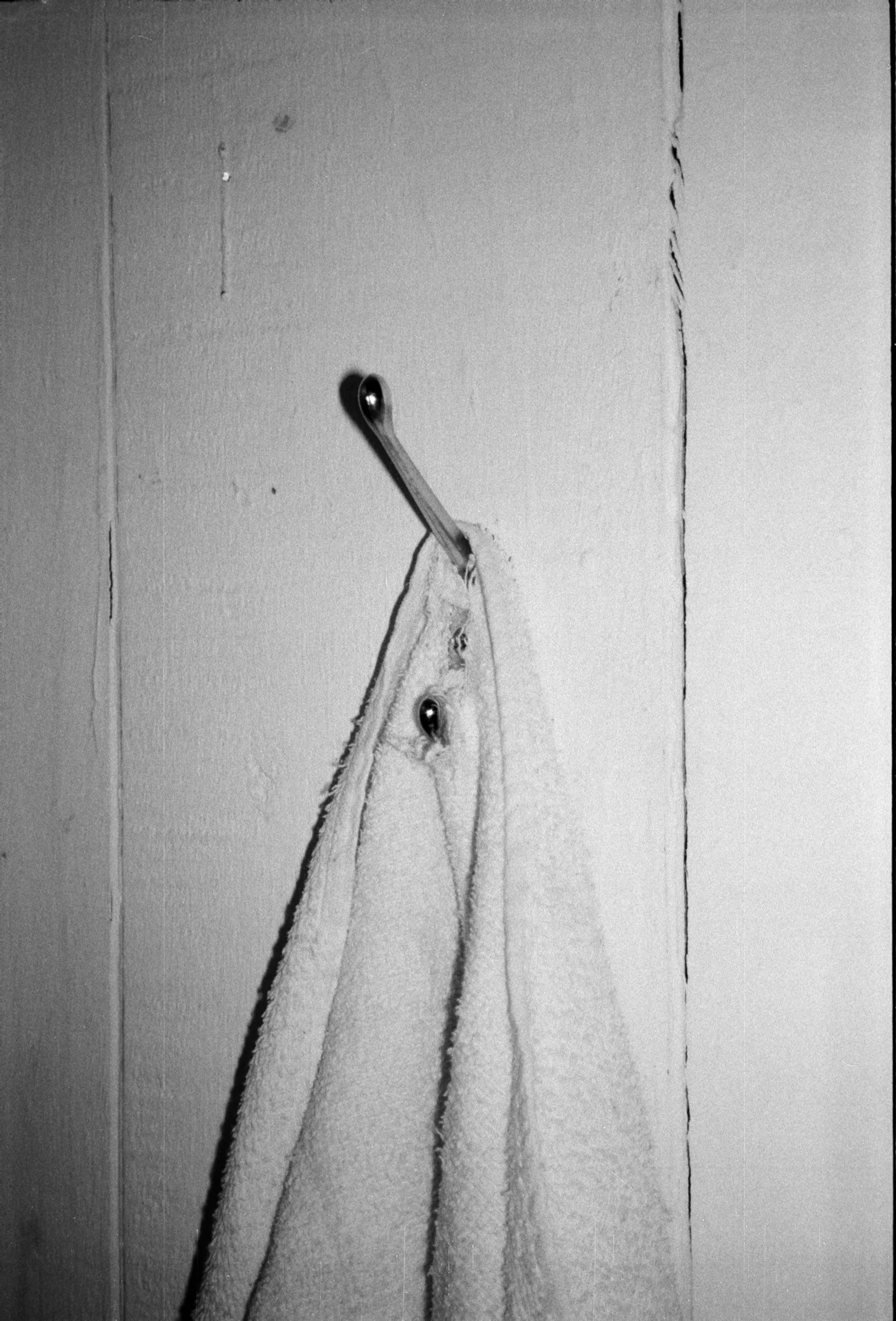

In this wandering, I keep encountering scenes that mix chaos and humor, which feel increasingly familiar to me. The Chilean term maestro chasquilla is used to describe someone who solves problems with great creativity despite lacking the proper experience or tools. We invent makeshift formulas and contraptions to tie a door, connect an electric cable, or even expand a house. It’s about acting with whatever we have at hand, and you can see it throughout our history. I feel that this way of responding to basic needs is capable of shaping the imaginary of a family, and why not, even of a nation.

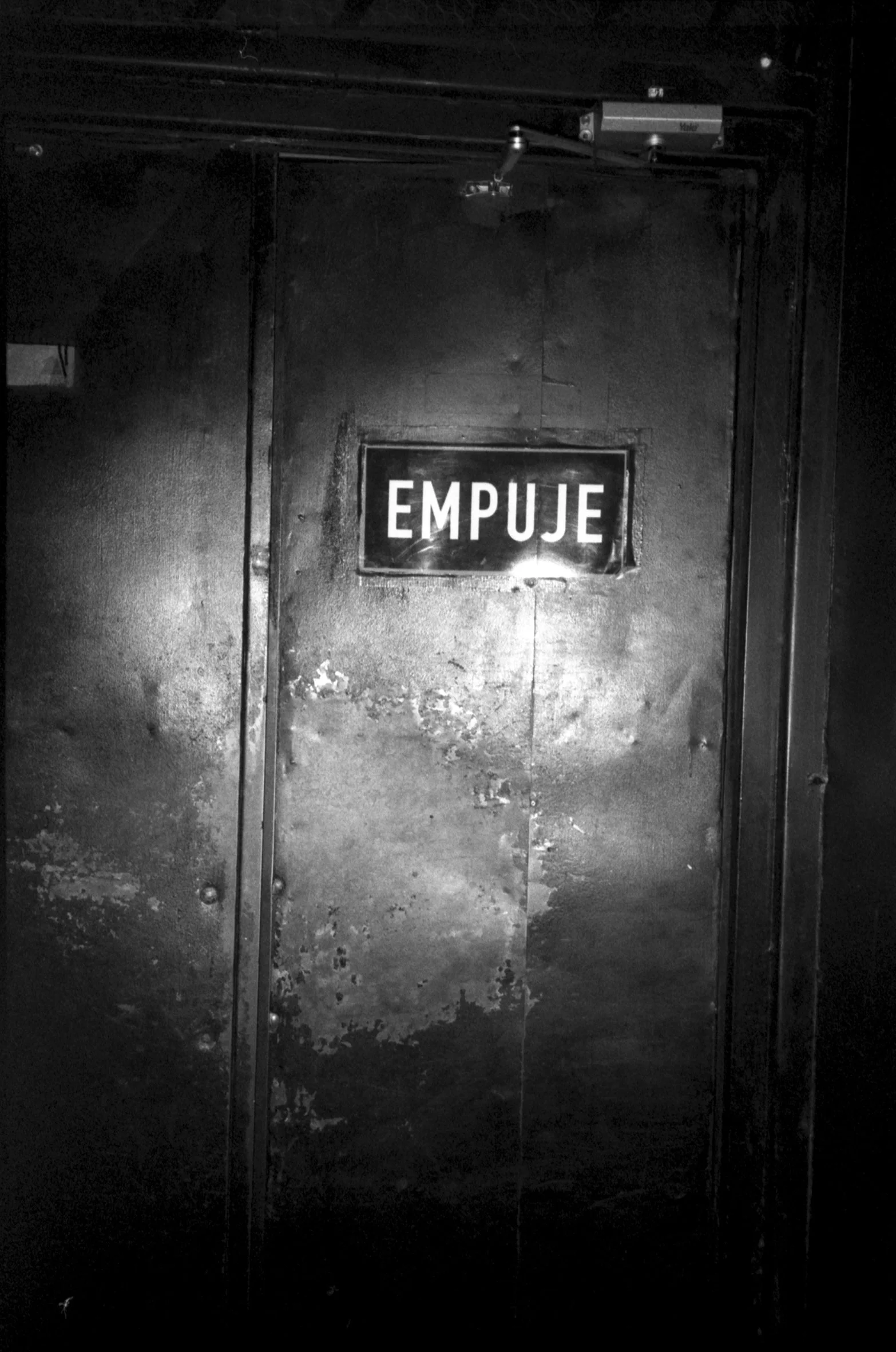

I react to the obsolete pot tied to a fence to feed stray dogs, to the design of a window, or to the particular wear of a door. I make an effort to reclaim this creativity with pride, and not as an object of intellectual mockery. I think of it as a return to my childhood in the neighborhood: the improvisations my mother came up with to raise us with what she had at hand, the five different ways to open the door of my house when I forgot my keys, or the clotheslines woven into peculiar shapes. This sense of belonging is fundamental in my artistic decisions. I see it as a very personal responsibility, and from there I discover my interests.

PAPANIKOLOPOULOS: How do you encounter architecture and the form of the city as a kind of resistance? In your images, there seems to be a tension—a dissonance—between what should exist in order, and how it nevertheless survives in a chaotic state. There also seems to be a correlation between the sense of belonging and systems of forced habitation. I’m thinking of entrances, doors, signage… what do these elements mean to you?

VERGARA: What is out of place is a form of resistance against the homogenization of our planet. Observing elements that don’t belong is mainly a way to preserve a connection with what is real, with what exists as a human work, a fracture, a chaos.

<> RODRIGO VERGARA is a Chilean filmmaker and photographer. At eleven, his father taught him how to use a Zenit 12XP. He shot his first roll photographing friends perched in trees. He never saw the images, but a couple of them stayed etched in his memory. He deepened his practice in photography while studying film, and has worked as a lighting technician across different corners of Chile. Along these travels, he’s developed a personal relationship—expressed through analog images—with spaces in constant transformation. In 2023, he published his first book, Hotel (Ediciones La Visita). He has contributed as an editor for Revista Oropel and is currently working on his new photobook, Hasta acá llegaba el mar.