SALON PHILIPPE

(Words) YOUSSEF BASSIL

(Photography) GEORGIA MCHAILEH

*Sassine, Achrafieh, Beirut

Athens Design Forum presents ‘SALON PHILIPPE’, an interview conceptualized by Lebanese designer Youssef Bassil on the fractal identity of a barbershop (est. 1968) in Achrafieh, Lebanon. An anatomy of the interior works in material counterpoint, affixed by years of quiet fortitude – the original Lebanese-made cast iron barberchairs, chrome-dipped and baptised with a signage of ‘Venus’, are reflected in the softness of formica walls and melamine counters. In Bassil’s composition, an anthology of belonging traces the disappearance of citrus trees and grape vines as the city center of Lebanon ever-rises in the portrait of Philippe Aaoun, ‘SALON PHILIPPE’.

“With fascination, I listened to Philippe talk. This little shop had seen a neighbourhood grow, and people come and go. Its walls had paid the price of wars, and its windows had been shattered and replaced many times. And yet, it still stood. As it had been designed in 1968.” Youssef Bassil

In September of last year, after three years of living abroad, I moved back to Beirut.

Many businesses I knew and loved had shut down, while new ones, completely alien to me, had popped up all around the city. The places I frequented and those that just felt familiar had simply been replaced: I had lost my landmarks.

Notably, my barber had left the country; I wasn’t the only one to have succumbed to the allure of exile. And as my hair grew uncomfortably long, I struggled to take the leap and just trust somebody new with scissors near my head.

“Go to Philippe,” was my father’s recommendation.

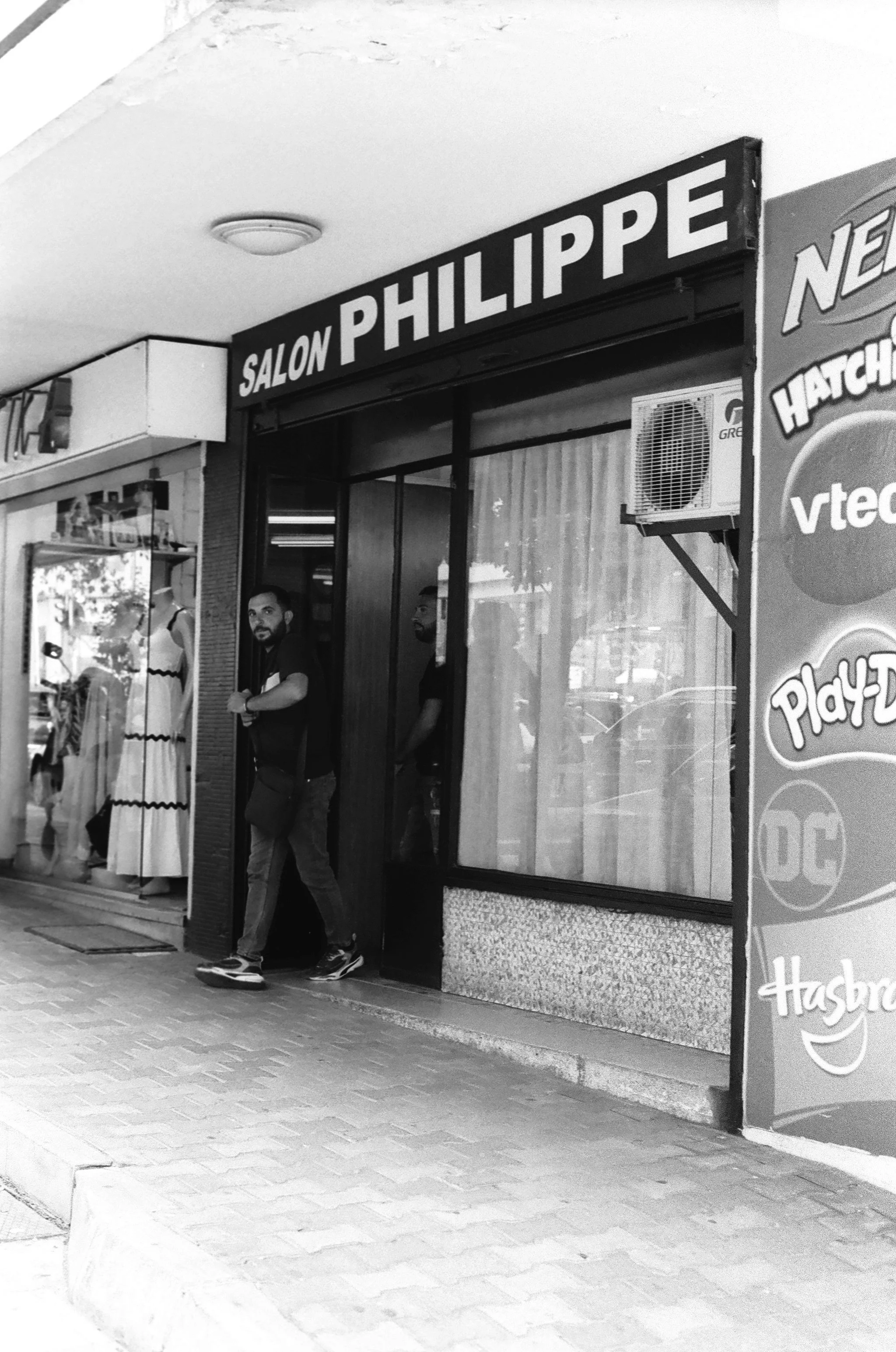

I know Beirut’s Achrafieh neighbourhood like the back of my hand, especially the area around the busy Sassine square. So I was surprised to have never even noticed that little barber shop on a street I had been up and down so many times in my life.

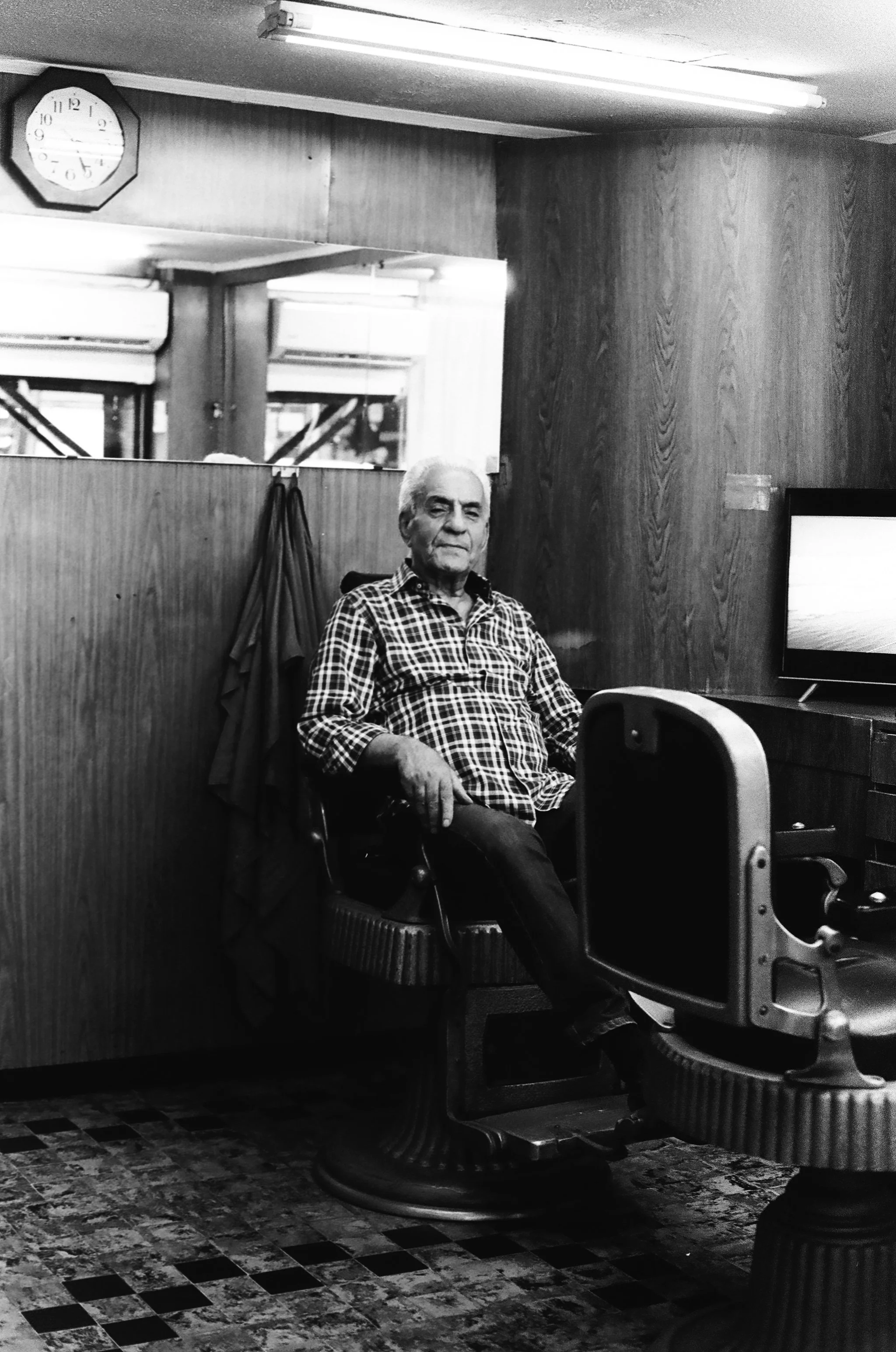

It’s an unassuming little space, nestled in the shadow of the balconies of an equally unassuming 1960’s-era building. In white lettering, the words Salon Philippe adorn its glazed façade framed in black painted steel and beige-brown tiles. The interior is veiled by a thin white curtain, revealing only the rough outlines of a barber shop. As I push the aluminium handle, I discover a small room, not bigger than six metres by four, entirely clad in antique (1) composite boards laminated in faux-mahogany melamine.

On the right is a flatscreen television (out of place in a room from a different era) tuned to Arte. On the left, a well-dressed man with slicked back paper-white hair stands up to greet me. After I had quickly presented myself and mentioned that my father had sent me to him, Philippe invited me to sit down on one of the three barber’s chairs facing the room-width mirror. I explained what needed to be done, and he got to work, the sound of his (wired) trimmer buzzing around my skull muffling the noises of the city outside. And as I sat there, I asked about the salon.

With fascination, I listened to Philippe talk. This little shop had seen a neighbourhood grow, and people come and go. Its walls had paid the price of wars, and its windows had been shattered and replaced many times. And yet, it still stood. As it had been designed in 1968.

As I got up and paid the man (who had perfectly executed my haircut), I knew I had found a gem. I have since become a regular at Salon Philippe.

When I was approached months later to write a piece on Beirut, I knew that I wanted to revisit Philippe’s story. And so, I went to get a haircut for Athens Design Forum.

The following interview excerpts have been translated into English from Lebanese Arabic.

[It was a warm May morning. Philippe welcomed me into his shop as per usual. I had passed by a few days earlier to ask him if he would agree to be interviewed; so as soon as I had set up the recorder and sat down in the chair he was ready to speak.]

PHILIPPE AOUN: The story of this shop starts in the year 1968, on the 16th of May. It was on the same day as the attempted assassination of President Camille Chamoun. I was 24 at the time, and I bought the business from a barber who could no longer work because of an illness that prevented him from being able to stand for very long. Once I moved in, I made some modifications to the space, and since then, hamdellah (2), the shop is as it has always been and it is still running.

YOUSSEF BASSIL: Before that moment, you were already in the barbering business?

AOUN: Yes, I used to work at a well-known barber shop called Faubourg Saint Elie, in Notre Dame de Lourdes Street in Ain el Remmaneh. I worked for them for about two years. And as soon as I felt worthy of it and felt that I had mastered the craft, I decided to start my own place.

BASSIL: And at the time you already lived in this neighbourhood?

AOUN: I’ve been here my whole life. My father was born here, and so was I.

BASSIL: And so when you bought the store, how much of it did you change?

BASSIL: I would say I changed about forty percent of it initially. The piping on the ceiling was apparent so I hid that. I clad the wall in formica (3). In those days formica was extremely trendy, so I picked that colour and stuck to it for the entire shop. The shop also didn’t have air conditioning, and I had that installed. Neither did it have a boiler for hot water, so I did that as well. Basically, when I got here it felt incomplete. And I just finished it all in a way.

BASSIL: You told me in the past about a shop you knew somewhere abroad on which you based the design for this one.

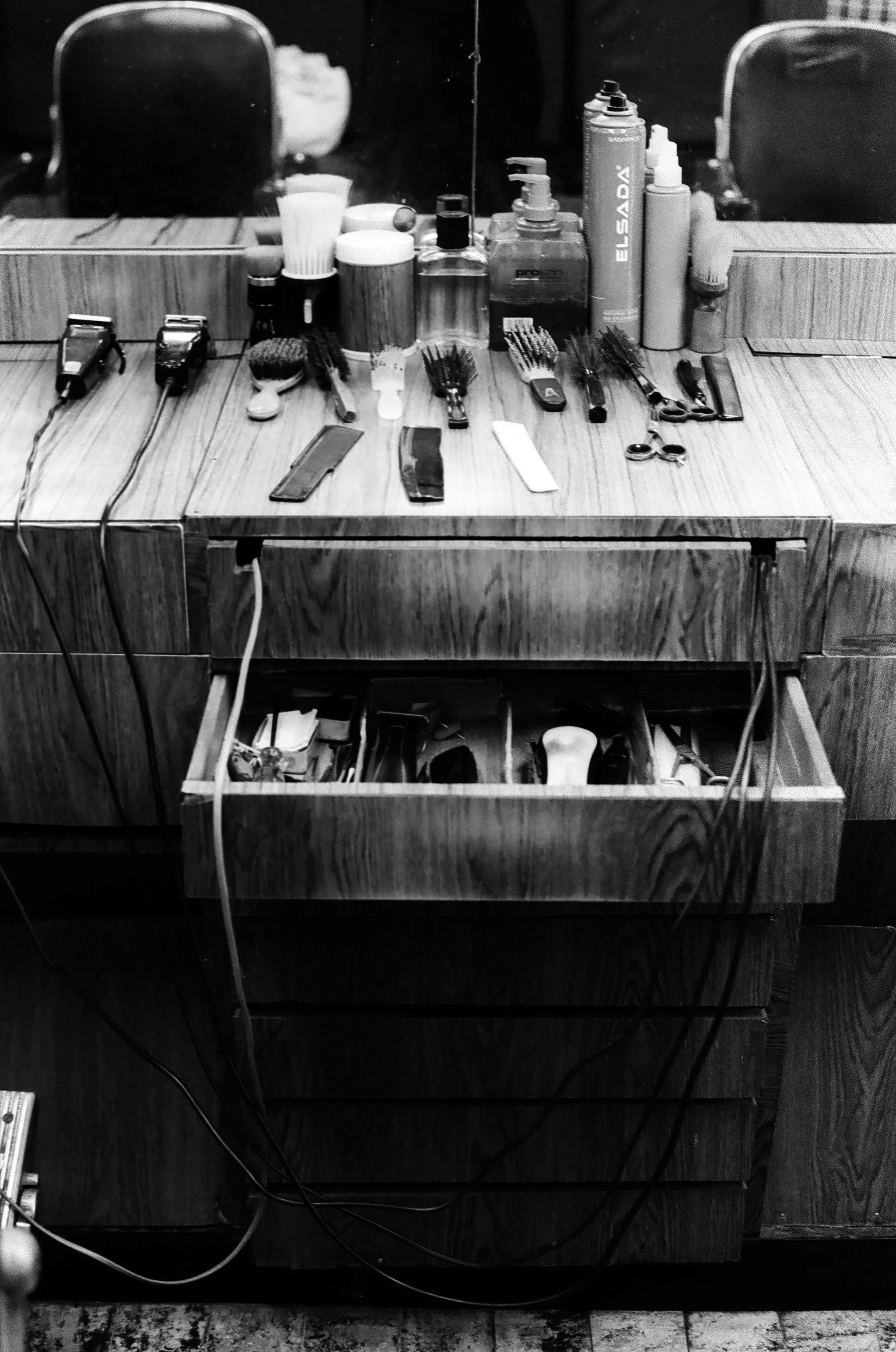

AOUN: Yes, that’s true. I asked for pictures so I could reproduce some elements. My favourite by far was the way the sinks were made. The way they are hidden inside the cabinets. I loved the idea of hiding them, it really appealed to me.

[In fact, the sinks are a striking feature of Salon Philippe. The first time I walked into the space, I wondered where they were or even if there were any. Facing the chairs and below the mirrors, the melamine-clad counters look completely mundane – but they are in fact hinged and act as movable covers for the washbasins. A truly elegant system!]

BASSIL: And where was that shop?

AOUN: It was in… in one of the Gulf countries. I must say, I don’t really remember which one.

BASSIL: Since then, what have you changed here? Or is it still as it was?

AOUN: The overall system is exactly the same. But during the war (4), glass would break, walls would get punctured, the false ceiling would collapse, the lights would fall… The war was a real struggle for us, and it constantly showed us new forms of destruction.

But no, otherwise it’s all the same. Visually, it’s the same. I always tried to preserve the original look every time I had to rebuild something here. Even the chairs are the same. These chairs are made in Lebanon, in Gemmayze (5) in fact. The owner was called Joseph Chamoun, a great guy!

[These chairs are unbelievable. Truly, marvels of craftsmanship and exemplars of a seemingly lost ability to build things locally and to build them well. Cast from iron and then chrome-dipped (a chrome effect today mostly tarnished into a wonderful patina), every element of them is a moving part in a mechanical system that has endured decades of daily use. These chairs are the kind of objects you look at and immediately trust.]

BASSIL: I wanted to get to the chairs.

AOUN: He shut his business down. His children didn’t want to take it over.

BASSIL: And do you think they’re still in Lebanon?

AOUN: I have no news of them. I was only friends with the father.

BASSIL: And did he only make those chairs?

AOUN: No, he made everything. He was specialised in equipment for barbers and hairdressers. He would also design and do the execution for the interiors of barber shops and salons. He was very good at what he did, Joseph. But God didn’t give him good health and he died quite young.

BASSIL: When I think of Gemmayze, I really don’t think of industries at all.

AOUN: It has changed tremendously. Of course, now it’s all restaurants and bars and nightclubs. But even at the time, it wasn’t a particularly industrial area. His was the only workshop that I remember being there.

BASSIL: You told me that in recent years, a lot of people passing by in front of your shop try to get you to sell the chairs to them, right?

AOUN: Yes. One time this guy showed me pictures of his house and living rooms. It was full of antiquities like those clothes irons that would be filled with hot coals, rotary telephones, do you know what those are?

BASSIL: Yes, of course.

AOUN: The guy was clearly very interested in antiquities. A collector it seemed. He begged me: ‘Philippe when you want to sell those chairs call me first!’ I told him I would, but it isn’t time yet.

And you know, I get him. They’re great chairs! Barber chairs today break your back.

At the time, I paid six hundred liras for each one of them. So eighteen hundred liras for the three of them (6). I paid half upfront and the rest was on credit, seventy liras a month. I’m talking liras! (7)

Now, a single chair would cost you over a thousand dollars. And it would most likely not be as good. I don’t know.

This is iron. New ones are aluminium. This chair you’re sitting on is so heavy, I don’t know how many people it would take to lift it.

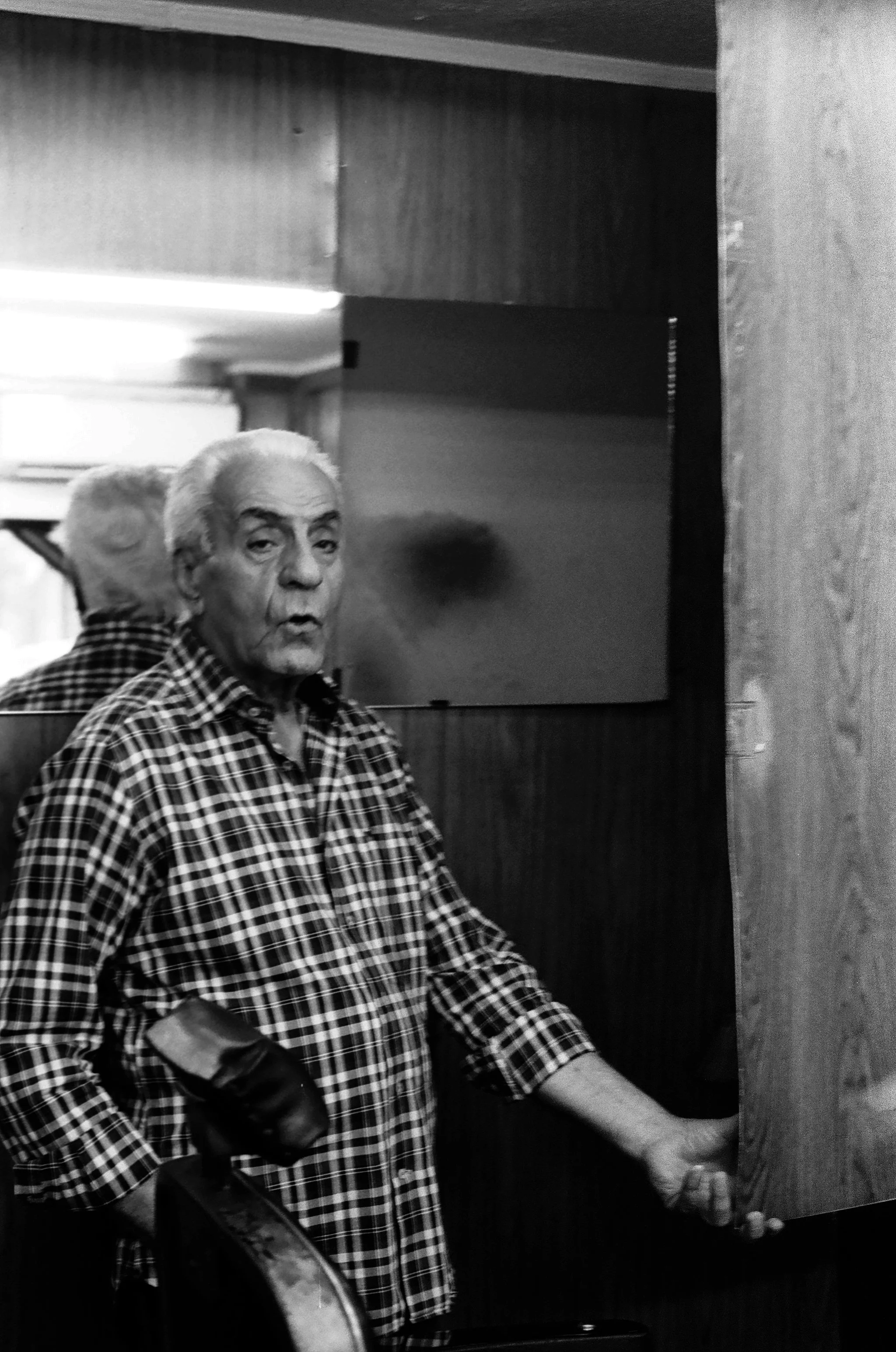

[Our conversation naturally fell into silence. As the trimmer buzzed around my head and the city outside continued to flow to the sounds of engines and horns, I held my next question back. In the mirror I could see Philippe’s face. He seemed to be hesitating, but here was a direction he wanted to take.]

AOUN: During the war sometimes I’d think: ‘maybe now’s the time to change the chairs, change the décor’. But whatever money we made went straight into repairing damage on the shop or our home! Every month or two we’d have broken glass or more – looking back it was terrifying. Having lived the war is very different from having heard the stories. It was difficult. Very difficult.

BASSIL: I can only imagine…

<> “During the war, I’ve probably replaced the windows here ten to fifteen times. When I’d call the glazier, all I’d have to say is ‘Philippe here’ and he’d know what to do. He didn’t need to come get measurements, he already had them.”

AOUN: During the war, I’ve probably replaced the windows here ten to fifteen times. When I’d call the glazier, all I’d have to say is ‘Philippe here’ and he’d know what to do. He didn’t need to come get measurements, he already had them. Not a month or two would pass by without him having to be here. Explosions would happen all around this street. And these explosions were so strong that even distant deflagrations would be enough to shatter the whole facade.

But since then it has only happened twice. Once when they assassinated the head of intelligence, Wissam al Hassan in the street just around the corner (8) – the whole shop was badly damaged. Then again as a result of the port blast (9). Also terrible damage. Definitely more than during the war, especially in one hit.

But hamdellah, we’re still here. I pray that nothing of the sort ever happens again to all of us.

BASSIL: I sure hope not!

[Silence again. This time, it felt like he had said what he looked to say. A horde of impatient drivers outside all simultaneously sounded their horns in the traffic, jolting me out of my muteness.]

BASSIL: And so this is a neighbourhood you know very well.

AOUN: Absolutely, I’m from here!

BASSIL: How much has it changed?

AOUN: It has changed one hundred percent. All of it.

Initially, this was a neighbourhood of small one-floor homes surrounded by gardens. They all had fruit trees and kitchen gardens. Many of them also had water fountains.

Now it’s all tall buildings and concrete. It’s full of strangers (10). Back then, you could ask me where the house of so and so was and I could tell you exactly. The homes were as many as the few local families. I wouldn’t call it a village, but it was definitely not a city. Maybe it was a suburb. A suburb of Beirut. It was beautiful. Now I don’t really like Achrafieh. This traffic and crowdedness, I hate it. I mean, to be fair, it can be beautiful because it can now be considered as a central point of Beirut. But it was all sweeter before.

BASSIL: But at what point did you feel this change started to happen?

AOUN: Achrafieh started changing after the war of 1958 (11). Those were the days of Gamal Abdel Nasser (12), Camille Chamoun was president. Back then, for the first time, Christians who lived on the western side of Beirut all wanted to move to more predominantly Christian parts of the country, and that accelerated construction in Achrafieh.

This war divided the country. That’s when we first started to see Christians moving to Christian regions and Muslims to Muslim regions. That’s the big mistake that happened in Lebanon. People no longer knew how to live together. There were grudges. What a mistake.

BASSIL: And the building we’re in, when was it built?

AOUN: I think… 1961 or 1962. It was still quite new when I arrived here. I’m eighty now, I’ve been here for fifty-seven years!

BASSIL: What was there around you? What did the street look like?

AOUN: At the corner of the street, underground, there was a cinema called Le Lido. And the stores… pretty much all of them were different. There was a butcher across the street. Where the pharmacy is today, there used to be a snack bar that made grilled chicken, manakish, lahmajuns… There was also a shirt-tailoring shop. I remember a great shop also that sold home and kitchen equipment, the owner was called Haidar Ghamlouch, he was from the south – a Muslim man who moved here at the time with his family. It didn’t matter to anyone where he was from. He had an excellent business, and everyone knew him. He had moved back here from Brazil, which is where he had met his wife. Lovely people, I wonder what has become of them…

BASSIL: Are there other people originally from the neighbourhood who are still around?

AOUN: No, not many. Mostly grandparents like me.

Take my children for example: I have two boys. They were not able to buy homes in the area. The prices of apartments here were reaching above the million-dollar mark. For a quarter of the price they could buy great homes, bigger and more comfortable, just outside the city.

So all of our children are gone from Achrafieh. It’s too expensive.

So yes, it has changed. Completely changed. It was beautiful. A village in a city. You would feel so far from the city, in the mountains. But then you were less than a kilometre away from the city. The whole city – the whole country was beautiful like this. Ras Beirut, Hamra, Ras el Nabeh, Kantari (13), all of these neighbourhoods were like that.

BASSIL: And have your clients changed?

AOUN: Of course. A lot of time has passed. I mean, for example, you and your father have been coming here a while but you’re not very old clients all things considered. I’d say almost half of former clients have left the country.

Business was different. The clientele was more well-off. And young men all leave the country for work now. But that’s a general thing for the country. Some of them never come back.

God blessed me; my sons both went abroad to study and work, one as a doctor and one as a lawyer; but they have both returned. They love it here. But some others just find their place outside.

[He pulls a small mirror from a drawer to my left and shows me the back of my head. We discuss the length and finishing touches briefly before naturally getting back into our discussion.]

AOUN: All these things I’m saying… I haven’t spoken this much in the past three or four years! It all makes me nostalgic for the old days. The way this country was and the way it could have been. It’s sad. It really saddens me. You, even my kids, don’t know because you have never seen the country I have seen.

Lebanon used to be called the Switzerland of the East… and that’s not wrong! It really was. What a shame, what a loss. A country that spoke so many languages, foreigners would travel here and have it easy.

Today I get foreigners as clients, and listen, I didn’t graduate high school because both my parents passed away early, so they weren’t here to support me. But I can speak with them in French and English – no problem! They’re always very impressed.

My heart aches for Lebanon. This, what we see now? It is not the Lebanon I knew. It has nothing to do with Lebanon. What a loss. I worry about my grandchildren. I’m sure they’ll leave when it’s their turn to study. If things remain the same, what will there be for them to do here?

Let me give you an example: At my childhood home in the neighbourhood, which was also just one floor with a garden, we had vines. When the season came, I would harvest them and would have enough for myself and for my neighbours as well. There would be so many grapes we could have fed a village! Our neighbour across the street had loquats, prunes, and oranges. And once their seasons came he would do the same, send us a case. We would go over to each other’s homes and help one another – today you would call this village life, but this was our reality right here! That’s all gone now.

BASSIL: And what about that childhood home?

AOUN: Youssef, our home was where your building now stands.

BASSIL: Really?

AOUN: Yes. I sold this land to Joseph Zeidan, who was a hairdresser and a cousin of mine. He then had the building you live in constructed and sold it to your family.

BASSIL: I had absolutely no idea.

AOUN: Well, now you know! The place you live was once my property. When you think of this land, remember that it was once Philippe Aoun’s. The son of Emile Aoun, who himself inherited it from his mother, Tamam Zeidan.

It was a beautiful old house, made of yellow sandstone. We had so much to give to those around us. I remember I had a lot of artichokes. People could have just walked over and picked them, gardens didn’t have fences. Yet nobody ever stole a thing.

Now I live in an apartment down the street. Hamdellah, it’s been a great place to live. And I’m so glad that I rarely have to leave the neighbourhood. I don’t have to get in my car every day to go to work.

[At this moment, Philippe’s wife walks in, as she often does on her way back home from walks in the neighbourhood. She is a dynamic woman, always elegantly dressed. On this day, she was wearing a chic silk button-up shirt with tailored trousers and low heels, smiling at me while we exchanged pleasantries and as I explained to her that I had been interviewing her husband.]

“You know, at his age, Philippe could have retired a while ago. This shop is his property, and he could just rent it out. But he simply loves his work. He is very proud of what he does, and that genuinely makes me happy.”

AOUN: I really do love my work. Every day feels like the first. I don’t think everyone gets this feeling when they do what they do. It’s a simple thing. When I come to work in the morning, I’m happy. And I hope that this is how you feel when you do your own work.

<> YOUSSEF BASSIL is a product / industrial designer based in Beirut, Lebanon, and a graduate of ECAL in Switzerland. Grounded in observations of contextual realities (manufacturing, cultural, societal, archetypical…), the projects he develops seek to embody a sense of self-evidence through their form and materiality. As such, he rejects essentiality as an aesthetical pursuit, but seeks it as a tool for efficiency and narrative clarity. This approach carries through his practice –in artisanal, industrial, spatial, curatorial, and academic endeavors. @youssef_bassil

<> GEORGIA MCHAILEH is a Lebanese interior architect and photographer based in Beirut, working fluidly across space, object, and image. @georgia.mchaileh

Notes

I love that we live in a world in which melamine laminated panels can be considered antique.

Arabic for “thank God”. It can express deep gratitude, polite acknowledgement, or even resignation, depending on tone.

A trademarked brand of melamine laminated boards.

Here he is referring to the Lebanon War (1975–1990).

A historic neighbourhood located near the centre of Beirut.

In 1968, 1 US dollar would have been worth 3.15 Lebanese Liras. So Philippe bought his three chairs for the equivalent of 570 USD – a small fortune back in the day!

Today, 1 USD is worth 89,500 Lebanese Liras.

Lebanese intelligence chief Wissam al-Hassan, known for investigating Syrian involvement in Lebanese affairs, was assassinated in a 2012 car bombing in Achrafieh.

A massive explosion at Beirut’s port on August 4, 2020, caused by improperly stored ammonium nitrate, killed over 200 people and devastated much of the city.

He means people who are not originally from the neighbourhood.

A brief civil war in Lebanon in 1958, sparked by tensions over President Chamoun’s pro-Western policies and regional Arab nationalism, ended with U.S. military intervention and a political compromise.

Gamal Abdel Nasser supported the Lebanese opposition during the 1958 civil war by backing pan-Arabist and anti-Chamoun factions, encouraging protests and unrest through propaganda and political influence, though he stopped short of direct military intervention.

Different historic neighbourhoods of Beirut.