The Architecture of Armenian Lace ◯ In Conversation with Gassia Armenian

© 2024 Fowler Museum

In the cosmology of lace, the fortitude and diasporic identity of Armenians is present.

As if the threaded constellations are joined in an impermeable dance, the action of intent remains in engaged connection. Athens Design Forum speaks with curator Gassia Armenian on the conscious cultural multiplicity of lacemaking, and the spirit that arises from a craft where fingers and thread pulsate forward intricate webs of meaning. Knots act as a foundation in place of an architect’s timber, as Armenian women concentrated their efforts in transforming lace into a mobile infrastructure. A device of agency – lace was to be carried, transported, worn, strong as armor. Both translucent and revealing, Armenian lace performed a play of the senses that allowed for a prestige bathed in mystical and healing qualities. In Armenian cultural heritage, lace transforms into an embodied and intergenerational art that ensures the longevity of a tactile language that is resistant and adaptive – at once as strong as the hands that shape a new inheritance of form.

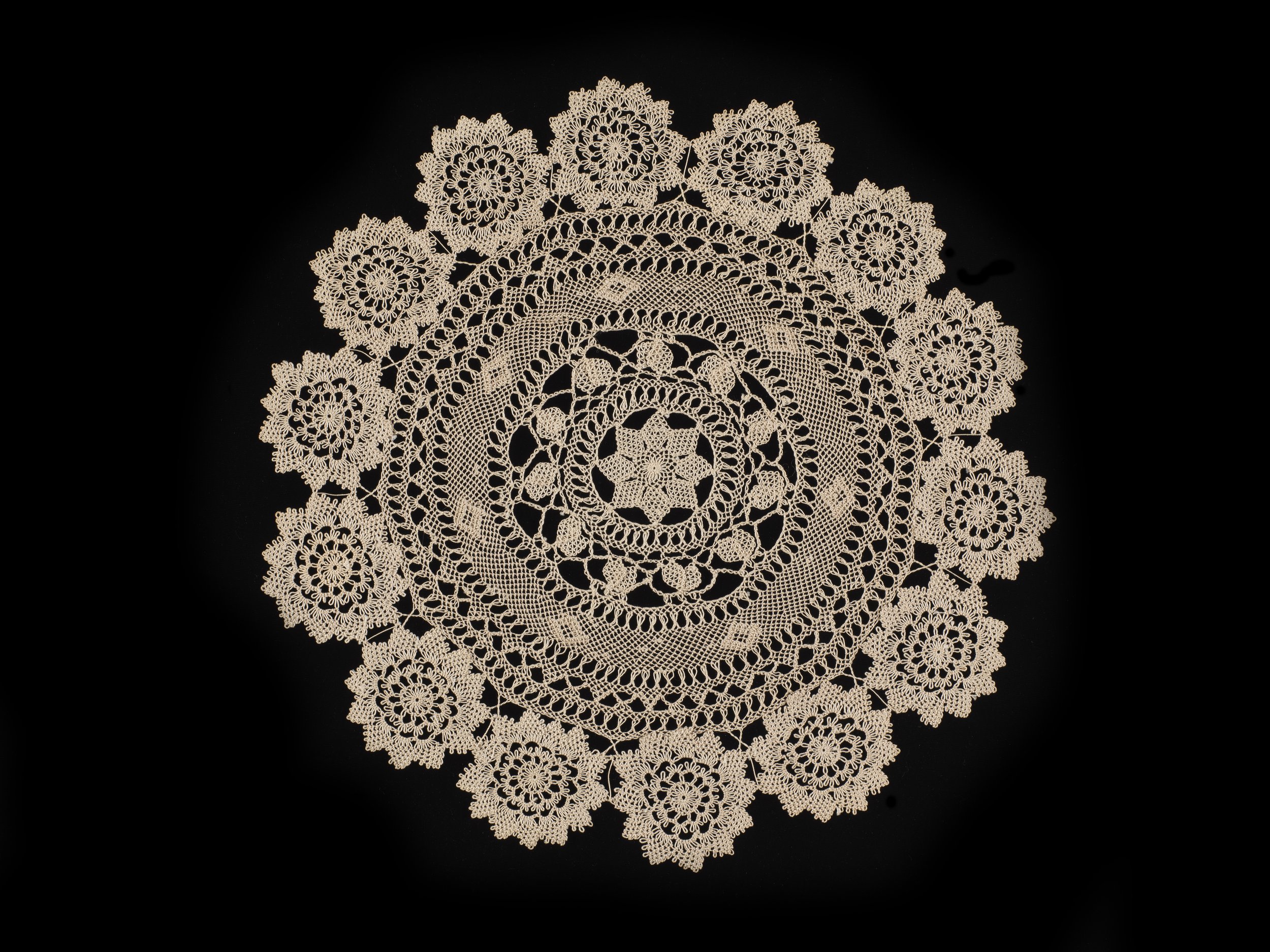

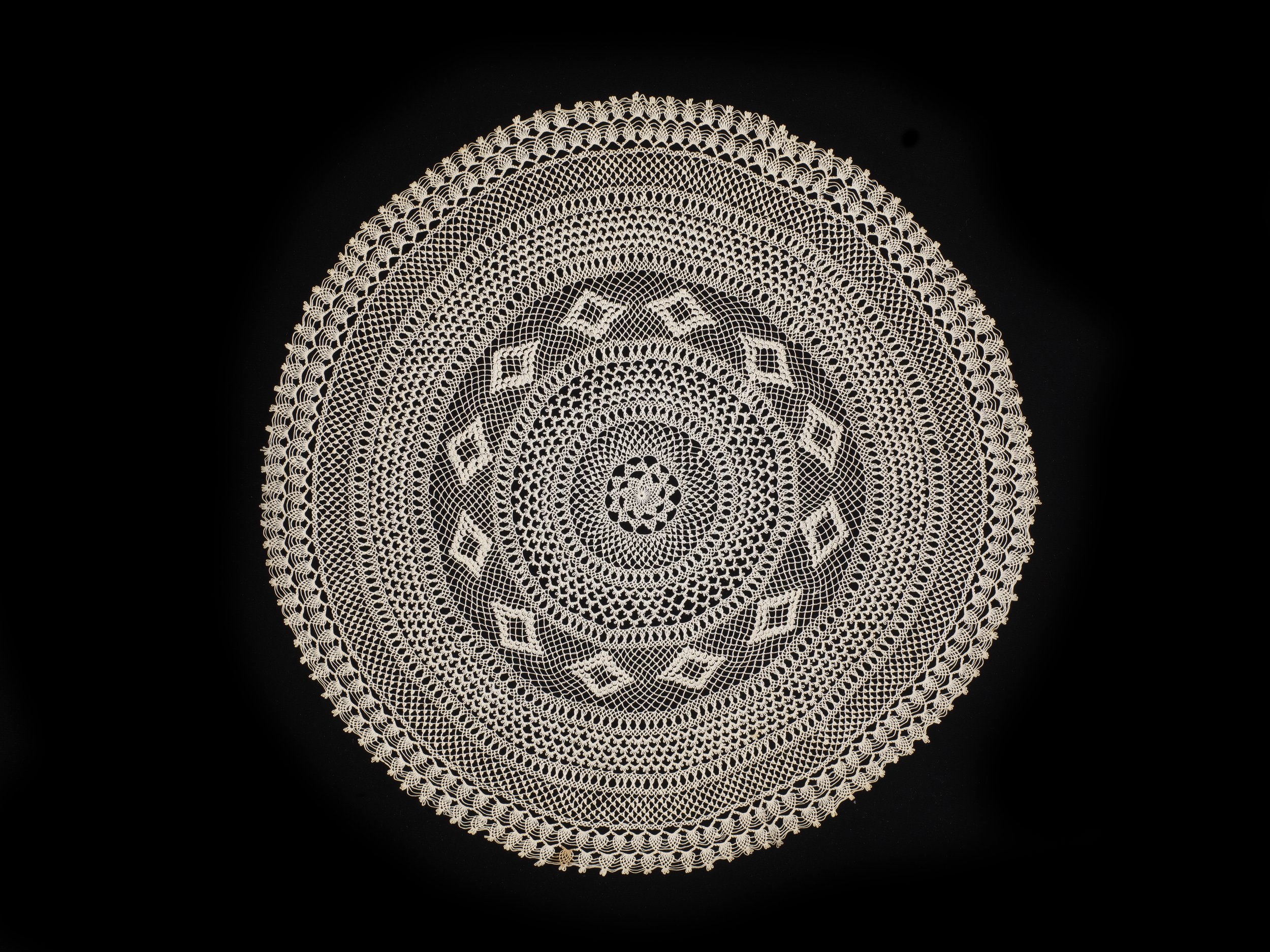

Consolidating these observations to a global stage, janyak, Armenian needlelace, becomes a universe mastered by the scale of tension through curator Gassia Armenian’s Janyak: Armenian Art of Knots and Loops within the Fowler Museum (April 23, 2023 - April 7, 2024). Presenting fourteen of the late Marie Pilibossian’s needlelaces, the exhibition positions the role of Armenian women’s art as a prominent voice in the chorus of immigrant identity. Bearing witness, Gassia followed a holistic entry into the history of the lacemaker, tracing her very steps across Armenia and the United States. Born in Beirut, Lebanon, Gassia’s grandmother is a genocide survivor from Gessaria (Kaiseri), sharing a symbolic association with the late Marie Pilibossian. The exhibition’s emphasis on the semiotic translation of motifs across needlelace is paramount, ushering in revived scholarship on a woman’s association with the natural world and the birthing of newly recognized motifs and symbols.

Across the metaphysical and the symbolic, Armenian needlelace follows women from life to death, onwards. Gassia articulates, “janyak is a thread that links many lives together, from mother to daughter, as it is an art that has been transmitted over generations and is still contributing”. The mystical powers it held were a good omen: janyak was created to embellish the baptismal garment that a baby wore and the frontal piece of nightgowns in the bridal trousseau. Its religious connotations saw it as an essential donation to churches, used to cover the host, to hold the cross with a janyak-embellished handkerchief, and to frame icons of the Virgin Mary or Christ. Within the diaspora, janyak appears in the hadig (tooth ceremony), through a baby’s head cover. Gassia contends, “Within hadig… when the first tooth is dropped, we make a wheat-based dessert decorated with walnuts, raisins, and then place different objects of [variant] trades, allowing the baby to choose one as a foreshadowing of the child’s future profession.”

Gassia concludes, “You are building, and it must come from within you. It is an art form where you need to fully concentrate as it is a meditative process. A well-executed needlelace has to be flat (no puckering, no gathering here and there) and it has to be even. It is almost a cross-section between structural engineering and needlelace. It is purely a universe that your strength builds…and it starts by wrapping the thread around your finger, threading the needle, then starting to make the knots that form the central main element of the janyak then from there making the loops from center to out, and always from left to right. You leave the evil back and go towards the positive.”

Reference of Yerznka (Երզնկա)

During Athens Design Forum’s research to prepare for this feature, Panorea Benatou, Curator of Manuscripts and Rare Books within the Benaki Museum, shared a rare illuminated Armenian lectionary from Erzikian, historically Yerznka (Երզնկա) (27,5 X 18 cm, 1581, TA 321). The purple-ink inscription of a Greek baker (Nicholas P. Kalogeridis) references the 1915 Turkish persecution of Armenians, and how Kalogeridis came upon as a witness to protect the future of the ecclesiastical artifact. With this reference of kinship across Greece and Armenia, we begin to speak with curator Gassia Armenian on the necessity of remembrance, that can be nourished only through the tangible.

© 2024 Benaki Museum Library

In 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne mandated the compulsory exchange of Greek Orthodox populations from Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace with Muslim populations from mainland Greece and the islands. Article 8 of the Treaty allowed for the transportation of properties by the affected populations. In 1928, the Fund for Exchangeable Community and Public Welfare Assets, commonly known as the Exchangeable Fund, was established to collect and distribute the refugees’ properties to the new refugee communities. Items of archaeological, historical, and artistic value were allocated to three museums: the Benaki Museum, the Museum of Folk Art, and the Byzantine and Christian Museum.

Dimensions of Bible: 27,5 X 18 cm | 237 folios (Total Pages: 474) | Date of Creation: 1581 | Provence: Erzikian

© 2024 Benaki Museum Library

© 2024 Benaki Museum Library

© 2024 Benaki Museum Library

“On May 29, 1915, a Friday, the Turks massacred all the Armenian citizens and villagers in the city of Erzikian. The city's population exceeded 15,000, while the villagers numbered over 8,000. Additionally, the Turks burned down the library of the Sourb Nshan. A soldier, in an attempt to take the cross as loot, hid the book under his coat and brought it to our bakery. He broke the cross from the top, took it, and left the book behind. In 1922, when the persecution of the Greeks began, many fled, but I remained until May 18, 1924, a Thursday. I departed from Yerznka for Thessaloniki and arrived in Thessaloniki on June 19. Nicholas P. Kalogeridis, Baker in Erzikian”

© 2024 Benaki Museum Library

THE STORY OF ORIGIN

Katerina Papanikolopoulos, Athens Design Forum: The story of how we met still brings me to smile. It was February of 2020 when I was a student at UCLA and I first heard of your wonderful work and character through the invitation of a Lebanese architect. Our connection continued even after I moved to Athens. Within the exhibition room at the Fowler Museum, we may finally discuss the worlds you have built and identified. How did the show originate?

Gassia Armenian: It started in the Fowler Museum store rooms. I discovered fourteen needlelaces which were donated to the museum by Mrs. Marie Pilibossian, an Armenian genocide survivor in 1980. Professor Avedis Sanjian, the Chair of the Armenian Studies Department at UCLA, coaxed the donation. The needlelaces were originally marked with ‘Izmir, Turkey’. This caused the samples to be wrongly attributed as Turkish as Izmir was among the last stops before Mrs. Pilibossian’s arrival to the United States. I had to dig much deeper to find out more… From the Los Angeles immigration archives to the Art and Crafts center in Beirut, Lebanon, and to Lusine Mekhitaryan (National needle arts artist of Armenia) little by little, I reconstructed the story of Marie Pilibossian and the story of janyak. I traced her all the way back…[finding] her intention for residency document and her citizenship document.

She emigrated to the United States in 1922 at the age of 25. She was born in Gessaria during the Ottoman Empire and was a survivor of the Armenian genocide, which took place starting in 1915. Miss Marie Pilibossian came to the United States aboard the Italian registry ship, the Regina d’Italia. She left Turkey from the port of Izmir and her first stop was Piraeus, Greece. I did not find any record of her disembarking the ship in Greece. All I know is that it took her 22 days to reach New York Harbor and then go to Los Angeles. At the LA county archives, I found out she was employed by the local government to help rehabilitate the genocide survivors in the city. Eventually, she became one of the founding trustees of the Ararat Home, an assisted living facility in LA. I also found out where she was buried at the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Hollywood Hills. On December 18th, I made a special visit to the cemetery with the intention of finding her final resting place. I was so happy…just as I found you, I found her. I could see her smile…

During the 19th century, janyak was part of the “curriculum” of marriageable-age girls alongside other domestic skills, as they had to know needlelace. After the genocide, missionary organizations who opened orphanages to give a safe shelter and home to the girls who had escaped, used needlelace as a source of self-empowerment, as a source for the girls to earn their daily bread. The missionaries would collect the completed janyaks and send them to their countries of origin for sale.

© 2024 Fowler Museum

Katerina Papanikolopoulos: How do you believe the multiplicity of lace form, across the Mediterranean, developed and grew outwards?

Gassia Armenian: Armenian women lived in the same neighborhoods as the Turks, the Greeks, and the Cypriots, wherein the term janyak was recognized as oya (Turkey) and bibilia (Cyprus, Greece). They are all the same textile art form. I am sure that they shared motifs, and many stories, together. Doilies were important objects in Armenian homes, decorating coffee tables, serving as lampstands, or draping over pianos. Negative spaces of the lattice work allowed furniture to show through and form a contrasting background to the lace. Such elements of household décor symbolized affluence and status not only in Armenia, but throughout the Middle East and the Mediterranean. They also demonstrated the ingenuity and talent of women. Each piece of lace incorporates an array of symbols and patterns, many of which appear regularly in janyak produced in Armenia and its diaspora, even though particular combinations of elements stem from the vision of each maker. Among shapes identified by scholars is a triangle that alludes to Mount Ararat, symbolic of Armenian homeland. Other elements represent eternity, the tree of life, Zangezur (a region in south-east Armenia), and Armenian folk dancers. In this way, janyak carried within its knots and loops understanding and affirmation of familial and cultural roots—a shared and treasured history.

The Khatchkar—Խաչքար—(cross-stone) detail carved by Master Poghos in 1291 C.E is located at the Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator at the Monastery of Goshavank in the Tavush Province in northeast Armenia.

Statuette of goddess Arubani, Kingdom of Urartu, 8th-7th century BCE, Bronze, H: 12.0 X W: 6.0 x D: 3.1 cm, Courtesy History Museum of Armenia, No. 1242

OF BRONZE & LACE – THE ARUBANI GODDESS

Katerina Papanikolopoulos: To see the photograph of the bronze Goddess Arubani, in her seated glory with arms upraised (a potential sign of blessing), added a heightened dimension to the exhibition – with delicate janyak tracing her body. How did you first come across this reference to the textile form?

Gassia Armenian: I came across one historic and scientific documentation in Armenia by Mrs. Serig Davtyan, a member of the National Academy of Sciences (Ethnography Department). In 1966, she published the first book on Armenian needlelace. In that book, she had a drawing of the Arubani statuette, claiming that the history of janyak dates back to this. When I saw the drawing, I started my search and located the statuette at the History Museum of Armenia and asked them about all the research that had been done for the excavation, including that they had found needles surrounding her. With this proof, the history museum seconded the assumptions, and perhaps it was the first time the actual photo of the goddess and the scientific caption, approved by the History Museum, had been exhibited through the Fowler Museum of UCLA. In December of 2023, I visited Yerevan, Armenia, and I had the opportunity to visit the bronze statuette of Goddess Arubani/Anahit, dating back to the 8th century BCE at the History Museum of Armenia. This was a momentous visit, because she held the key to the origin of needlelace in Armenia.

Her head cover flowing to her feet had the first embellishment of a textile with Armenian needlelace, janyak. Yes, this 12 cm bronze statuette, excavated at the fortress of Darabey, near Van, set the origin story of janyak. My previous research had led me to her, and I had the image of the statuette from the Museum in Yerevan, but seeking her, “in person” validated my research. The veil was translucent… Janyak gives you the ability to see… Janyak gives the property to see the actual lace part and the negative space [therein].

Seeing the statuette, in situ, short of hugging her, validated everything I had been saying. Talking about the photo removes from the reality… a photo is a depiction of the real object. The veil was not to cover her from the view of others…the veil with this magical janyak (and janyak is considered to have magical and mystical powers) draped all the way down to her feet, and that was a protective cloak. And the janyak in the guise of a fisherman’s net, captured all the evil and protected her body. There used to be a Eastern European tradition as well, where the bride would be covered with a veil all the way down to her feet, and it would have shining elements to deflect evil intentions and gazes.

© 2024 Fowler Museum

ON TRANSPERANCY, FERTILITY, AND MOTHERHOOD

Caressing the perimeter of the goddess’ body, the veil emphasizes transparency. She is the goddess of the land, of fertility, a combination of Hera, Demeter, Persephone…she is the mother goddess… she engenders life… just like Anahit, who later entered Armenian mythology. Later on, we have the Virgin Mary, who replaced the role of Arubani and Anahit and continued this blessing of giving life. In every single Armenian church, when you look at the altar, you will see the image of Virgin Mary holding baby Jesus. Whether we like it or not, we are a matriarchal society…it was during the Ottoman Empire when women became the property of their father or husband. In Armenia, in the highlands of the Armenian Republic, since Arubani until today, the mother is an important key figure in society.

TOWARDS A NEW MODEL OF EXHIBITION DESIGN

In the exhibition, I made sure it was with an upright orientation. Usually, any type of embroidery is exhibited flat or on a slant board, but I broke that mold. I said: “We are going to stand up, look eye to eye at these embroideries as each one is a universe”…the symbols and the motifs are the flora and the fauna and the constellations. Janyak is a microcosm of the universe.

We have to [access] the creator’s inner feelings, motivations..how Mrs. Pilibossian must have felt at that particular moment, and look eye to eye and admire. I made sure the plexiglass was slightly higher than my height with two-inch rivets holding the laces, allowing the light beam directed on the janyak to give a correct shadow of the janyak. That gave it life… the shadow actually gave it life… we all have our shadow side… and the janyak has its shadow side as well. The shadow is the spirit, in my opinion, of the person who created it. Two visitors, a mother with her eighteen year old daughter, told me that the Greeks whenever they do a piece of embroidery, leave an unfinished loop so the spirit can leave outside of it…so the spirit can be felt within the shadow and in the unfinished.

I included two needlelaces exhibited in the traditional way to prove the continuity from mother to daughter, two pieces that were saved from the burning house of Agnes Devletian during the civil war in Lebanon (1975). It was from a private collection and they were kind enough to lend for the exhibition. The exhibition is designed to be viewed from left to right (pushing to the left towards the right… it is like writing… the transition of thoughts towards positivity).

© 2024 Fowler Museum

ON MANIFESTATIONS OF JANYAK IN SPIRIT AND STONE

Katerina Papanikolopoulos:

The manifestations of janyak, across the statuette of Arubani and onto the monumental stone Khatchkars, trace a new lineage of the form – across mediums and modes of expression. What did this discovery convey to you on the multiplicity of language janyak allowed?

Gassia Armenian: After the discovery of the statuette of Arubani, I asked myself if janyak has manifested itself in other uniquely Armenian art forms since the 8th century BCE. Statuesque Khatchkars, cross-stones carved in soft, pliable tufa volcanic stone, were commissioned by the local noble princes to memorialize their good deeds. The blessing ceremony would be a landmark event for the prince's family. He would be accompanied by his princess and his children. The princess had a major role in the community because it would be she who would defend the town and provide food and shelter during adverse political conditions when the prince and his men were at war. Once it was carved, it would be transported to the courtyard of the church and it would be blessed. Multitude examples of church doors, carved in wood, replicate the motifs and the symbolism found in janyak.

More than fifty thousand khatchkars survive throughout Armenia, and no two are alike. Khatchkars are still carved today in Armenia and in the diaspora. Since 2010, khatchkars have been inscribed on the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage for their symbolism and craftsmanship.

An image of a khatchkar—Խաչքար—a cross stone-carved in 1291AD by master Poghos is located in the Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator in the Monastery of Goshavank, Tavush Province, northeast Armenia. It provides standing proof of reiterative design code. The art of janyak has manifested in many different media. Cotton thread has been the primary medium for the artform, and the needle has been the primary instrument, but Armenian artists throughout centuries have used the same design codes and intellectual software to transmit the visual language of their ancestors. The Armenian genocide master-minded by the Turkish Government in 1915 has not stopped. It has a new target, the Armenian churches, Khatchkars and monuments. In other words, the Armenian culture. Azerbaijan continues Turkey’s goal of annihilating the Armenians. On September 19, 2023, Azerbaijan invaded the territorial integrity of Artsakh, populated by Armenians. Every time I see a cross removed from the dome of a church, every time I see the altar of a church turned into a stable for donkeys, every time I hear of a maternity hospital blasted to shreds, my heart sinks. If this is not the genocide of a culture, then what is it? I am in shock. How can the nations of the world remain silent to ethnic cleansing, forced migration, and occupation of a sovereign territory? However, the mystical powers of janyak have the capability of rallying Armenians together in more than 106 sovereign countries around the world. Janyak will generate and cast a powerful net around the Armenians, wherever they are on planet earth! You cannot unravel janyak when you cut the embroidery with a pair of scissors. The knots protect and hold the loops tightly together. Similarly, some nations of the world have and will try to eradicate Armenians and Armenian culture, but the power of janyak will keep them together and help the Armenians to prosper and multiply around the world.

© 2024 Fowler Museum

Curator Biography

Gassia Armenian is the Curatorial and Research Associate at the Fowler Museum at UCLA where she conducts collections and database research to facilitate curatorial and scholarly endeavors and manages various aspects of planning and organizing museum exhibitions. She is the curator of the exhibition Janyak: Armenian Art of Knots and Loops and the photography exhibition, Remain In Light: Visions of Homeland and Diaspora. She also liaisons with domestic and international institutional and private lenders to the museum. Ms. Armenian has helped to mount many exhibitions at the Fowler Museum including, Striking Iron: the Art of African Blacksmiths (2018), From X to Why: A Museum Takes Shape (2013–2014), World Arts/Local Lives: The Collections of the Fowler Museum at UCLA (2014), Secrets d’Ivoire: L’art des Lega d’Afrique central (Fowler Museum traveling exhibition at the Musée du quai Branly, Paris, 2013), Central Nigeria Unmasked: Arts of the Benue River Valley (2012), Architecture of the Veil: An Installation by Samta Benyahia (2007), A Saint in the City: Sufi Arts of Urban Senegal (2003). Prior to her work at the Fowler Museum, Ms. Armenian was a Consultant-Project Coordinator at the US Agency for International Development for Junior Achievement of Armenia. Within this role, she developed and implemented civics-education training programs and teaching methodologies for principals and teachers from the Republic of Armenia in the United States and in Armenia.

____

No part of this website may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of Athens Design Forum.

Requests for reproductions or permissions to publish should be directed to info@athensdesignforum.com