The Choreography of Play ◯ In Conversation with Luna Paiva

In the lasting images of Argentine sculptor Luna Paiva, one senses the artisan’s relationship with landscapes of movement and the immateriality of a gesture shared amongst youth. Athens Design Forum invites Paiva to share a dialogue and photo essay on the choreography of play; how she imagined a sculptural playground for an orphanage in Amizmiz, Morocco, once the epicenter of the earthquake, in a collective effort towards reconstruction. In questioning the reality of creation, an introspection unfolds from the modeling process, assessing the body’s axis, and the reiteration of Zellige tiles to be ever-changing as the day travels to night. What began as a series of drawn black-ink portals were built to become a rooted monument – alight with the intention to transform whoever comes upon them.

Athens Design Forum, Katerina Papanikolopoulos: On the choreography of 'play'; How were the shapes a definite form? How did you change, adapt, and morph them individually and collectively?

Luna Paiva: It is true that there is a choreography that appears when kids interact with the sculptures. The ‘choreography of play’, I like that definition very much. At first, they didn’t know if they could play on or even touch the sculptures, but then a boy climbed and jumped from the top, and suddenly a myriad of kids were there to invent their form of play – passing through the portals, climbing, hiding, sitting. Suddenly the ‘play mode’ was on, the kids owned the sculptures, and a new perspective unfolded, effervescent and alive. I was there with my camera taking it all in: playing, smiling. I would thank them and they would thank me back. The feeling was overwhelming.

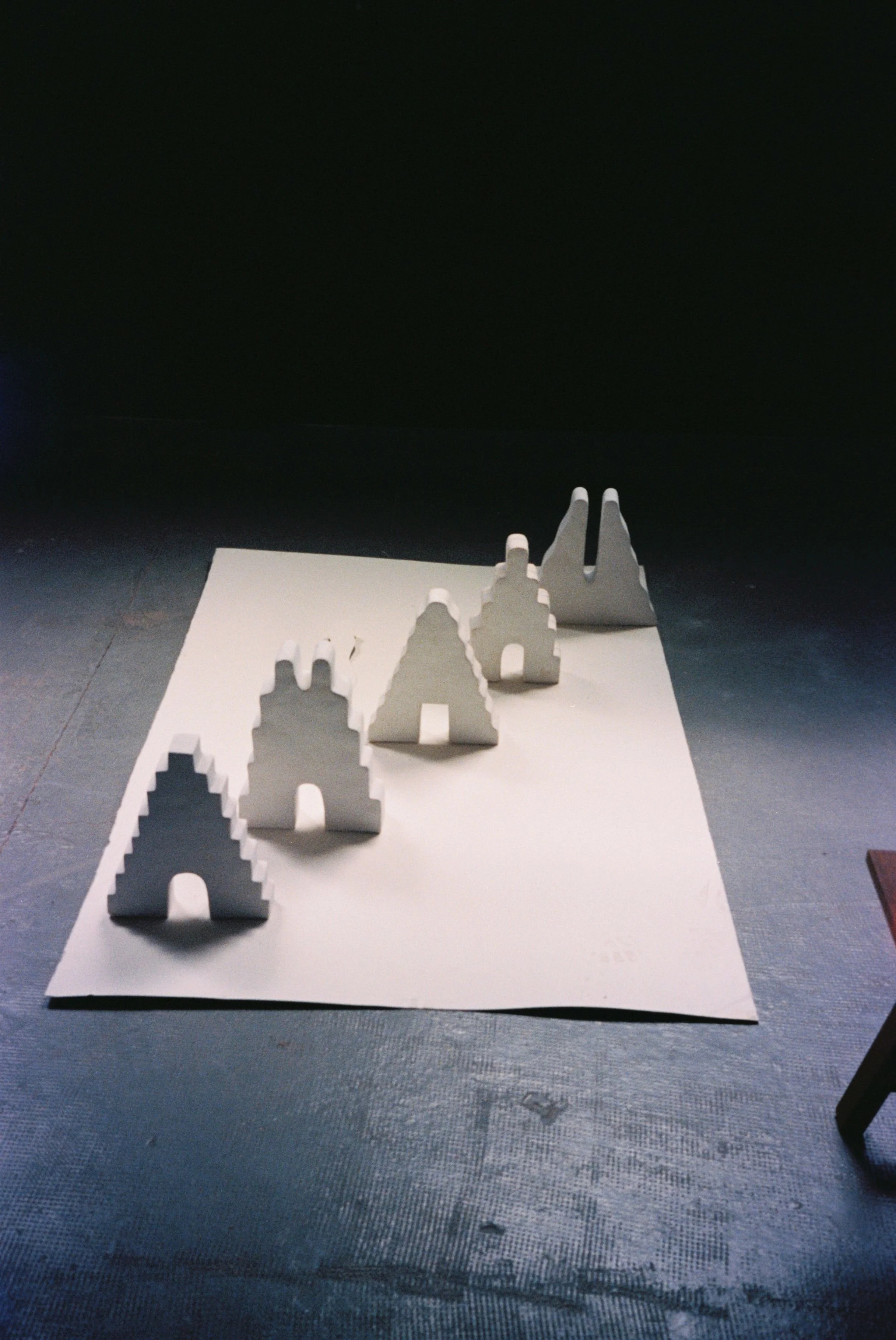

The first design is in my notebook: a series of portals in black ink, a path of transformation, each portal leading to a new stage, a new experience. I liked this idea so much that I made the models on a small scale in plaster. They were there waiting for a sign to be built in the real world. Two years ago, there was an earthquake in Morocco, and I needed to help but didn’t know how. Pablo Bofill, my husband, put me in contact with the building company SGTM and Elke Bardor who were at the heart of the construction of the orphanage in Amizmiz (where the earthquake hit the strongest) along with The Moroccan Association for Aid to Children in Precarious Situations lead by Touraya Bouabid. Suddenly it all made sense, the portals were meant to be there, to become a playground for the children.

ADF: Experiencing the effect of the structures with your immediate family, and sensing the spatial gravity of the orphanage; how was the process of collaborating? In what ways was the initial communication with the space formative to the final project?

LP: I had to adapt the sculptures for safety. I have a three-year-old and she was my reference; she had to be able to climb the easy bits, and I had to make the difficult ones unreachable. So, the first step is much higher to make it inaccessible for toddlers. The steps are deeper for stability purposes and the passageways are wider. I lowered the height from the original drawings so that kids can jump from the top safely. But playgrounds should include a challenging element, it should be stimulating.

My kids came to Morocco several times as I wanted them to be a part of the process. We drove through Morocco from Marrakech to the desert, from Casablanca to Amizmiz, and we went to see the construction site where they were building the orphanage. The village was devastated by the earthquake – people living in tents, and fields of olive trees dying; you could feel the gravity of people’s loss, both spatially and emotionally. The orphanage was the epicenter of the reconstruction and embodied the village’s spirit.

ADF: On the materiality of tiles – describe the selection of coloring, mosaic orientation, and historical weight of the item.

LP: The Zellige tiles, Moroccan glazed terracotta handmade mosaics, were perfect for this project. This material brings together cultural heritage and craftsmanship that is very much alive. It’s a colorful, playful, and noble material, ideal for the outdoors. Local artisans prepared each color and applied the tiles to the sculpture. Together, we created a continuum of color for each sculpture, from darker to lighter.

ADF: How was the body an axis to develop the prototypes?

LP: The body, movement, energy. The key lies in how bodies discover the shapes and invent new ways to play. But the mind, triggered by visual stimuli, activates the body, which then comes fully alive in movement. The sculptures had to act on all the senses—visual, mental, physical—to create a vibrant kinesthetic moment.

ADF: References of structures; Describe the variant development methods, how did one influence the other?

LP: Black ink on a notebook, small scale models in clay to define the shape and balance, molds, small-scale plaster models, chalk drawings on wall for 1:1 scale to study the height and proportions, 3D models, concrete 1:1 prototype.

ADF: On working with local craftsmen – define your artisanal process.

LP: Learning from the artisans is always a fascinating process—taking in what they know and layering an artist’s perspective. It becomes a multidimensional experience for everyone. Understanding the craftsmanship, certain abilities, both limitations and rhythms. When I start a new project, I always start with the cultural context, the importance of respecting local traditions, and the financial reality. Space and time shape these parameters and create a framework for the project. Restrictions can help hone in on the essentials and then unleash a whole new creative freedom. In this project, Zina Smires from SGTM, the builder of the orphanage, was my guide. She is such a sharp and quick thinker, so knowledgeable about form and structure. It’s been a pure joy to discover Morocco, to work in Amizmiz, and to share exquisite meals with the kindest people. But it’s also been an adventure. I was taking photographs at one point and the local police escorted me to their headquarters, taking my passport. I had no idea why I was there. I couldn´t show them the photos because I was shooting on 35mm. In the end, I opened my camera, and in a very theatrical way, destroyed the roll by pulling the film out. I was released after that.

ADF: We always advocate to share narratives that may seem unexpected, if certain stories come to mind from the development process.

LP: All the ideas come from a fictional world, from the mind. I sketch in my notebook, becoming a form of rehearsal, where the ideas transform into clay models, and other shapes morph into bronze sculptures. They jump from one material to the other, in the same way that kids leap from one part of the playground to the next. I never know where these initial ideas will show up. Different projects offer places for my ideas to land, and I link them with all this potential ‘fictional’ material. Suddenly these two-dimensional sketches become real, tangible (and sometimes even meaningful).

Images courtesy Luna Paiva, 2023-24.

Luna Paiva was born in Paris in 1980. She holds a degree in Art History and Archaeology from Sorbonne University and studied film at NYU. Her artistic mediums are sculpture, installation, and photography, and her work has been shown through exhibitions in Latin America, Europe, and the United States. With permanent public sculptures in Spain, Argentina, and Morocco, in 2024, she inaugurated a sculpture playground for the orphanage of Amizmiz in Morocco and is designing a new playground to integrate a marginalized neighborhood into the city of Cotonou, Benin. In 2025, Paiva will premiere “White Portals”, a permanent public sculpture, for The Havana Biennial. lunapaiva.com