THE POTENT IMAGE OF YUGANTAR COLLECTIVE

Presenting the Premiere of Tambaku Chaakila Oob Ali (1982) and Sudesha (1983) in Greece

BIOS Cinematheque | Pireos 84, Athina 104 35 | Sunday, October 8th 7:00 - 8:00 PM

The screenings will include English subtitles; Q&A following.

Athens Design Forum (ADF) presents the premiere of India-based Yugantar Collective’s filmography in Greece with a double screening of the restored Tambaku Chaakila Oob Ali (Tobacco Embers, 1982) and Sudesha (1983). The films extend ADF’s 2023-2024 ANTHROPOS-TOPOS theme, deciphering how humans coexist with places at the proxy of design.

Tobacco Embers and Sudesha are resonant and emotive examples of how film deciphers the contours and shadows of women’s lives, revealing a potent image. Solidifying its position among the canon of ‘factory films,’ Tobacco Embers’ cinematographic emphasis on portals, doors, and gates alludes to the very structure of how systems of exploitation persist. Within both films, architecture, and landscapes of labor become signifiers of extractive, coercive, and penetrative conditions that inform women’s resistance. The films chronicle converging themes of labor practices in environments that span from a tobacco factory in Tobacco Embers to a Himalayan forest in Sudesha. Gendered connotations of labor are heightened and perforated as Yugantar Collective introduces a collaborative process of filmmaking that ensures the voices and actions of the female laborers still resonate today. Since their creation, the films have been screened throughout India in universities and female-led union spaces to harness temporal platforms of critical dialogues.

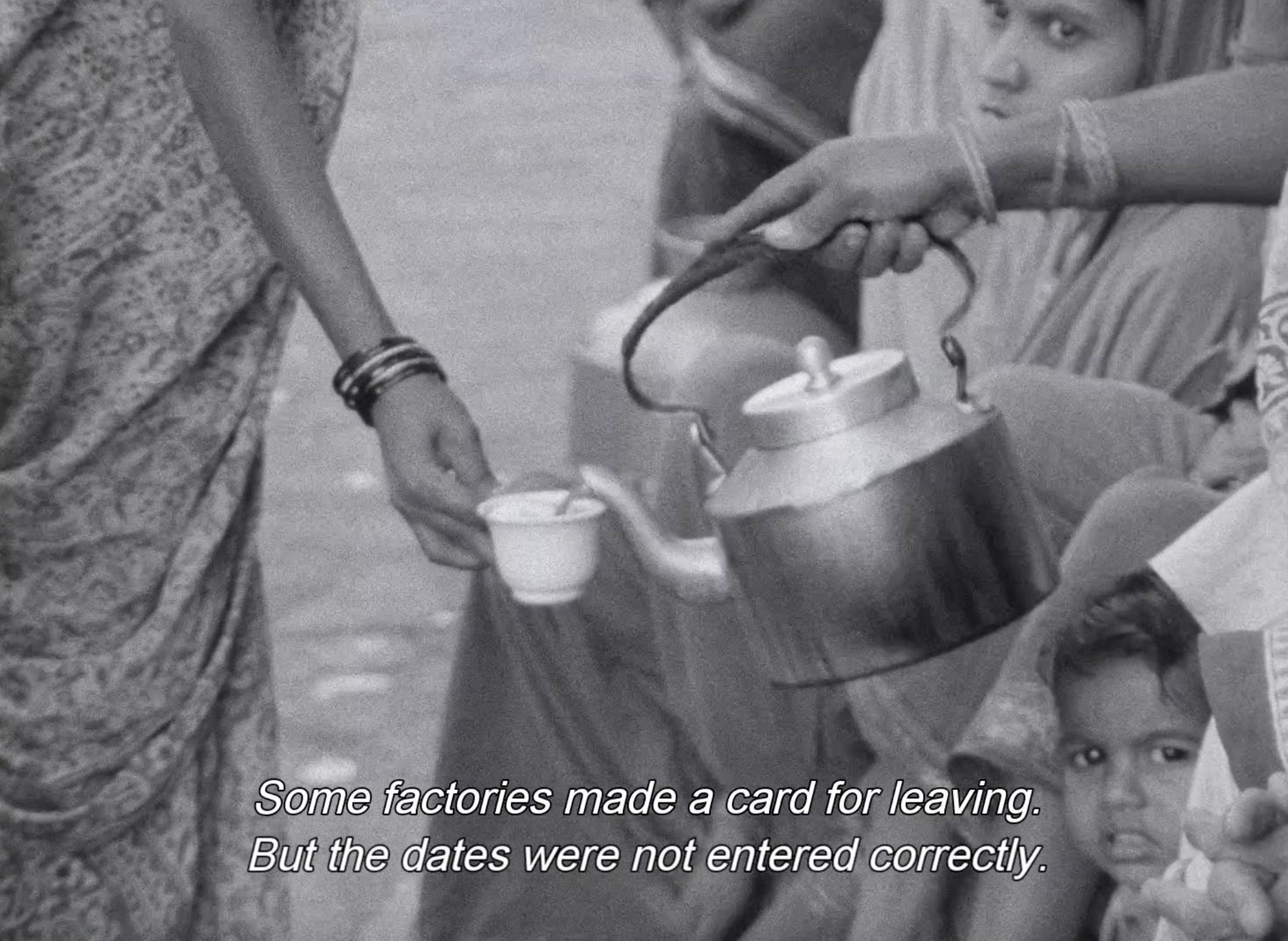

Tobacco Embers reveals the changing spatial orientations of Indian factories and how women laborers transform these industrial spaces into interiors of both refuge and refute. Porcelain plates and tea cups, byproducts of British colonialism and vestiges of the Indian caste system, infiltrate scenes of activistic rapport. Saris safeguard the protagonists when used as face coverings to exhume the harmful dust of tobacco. Woven basketry and large wooden planks extend the female body, adopting the rhythm of songs that consciously unify the women’s collective acts. The voices of the protagonists beckon a questioning of duty and morale, wherein ritual and alms of protection coexist with the dexterity of the trade. Pivoting from the visual weight of the tobacco industry to the collective gathering of the female workers within and outside their forced confinement proves a film of integrity, one whose perpetual intrigue serves as a catalyst for the power of being seen.

In Sudesha, a female village activist in the Chipko forest conservation movement is portrayed through the role of Sudesha Devi. Devi protests the changing ecology of the forest due to the introduction of imposing timber traders at the foothills of the Himalayas. With trees being used to make items such as tennis rackets, the film is a testimony to the impacts of colonial extraction for supply chains to native populations. As male partners left for work in distant territories, women led central roles in their communities. Viewers witness how the body becomes an integral instrument of labor that fuses the protagonist with the act itself – climbing trees, pounding wheat, sharpening knives, and collecting and carrying animal feed from regional plants. Unexpected uses of natural elements, such as a leaf transforming into a spout on a water spring, speak to the women’s relationship to the land and their quest to retain autonomy over their soil and customs.

For approximately 40 years, the extant four films of the Collective vanished from the public sphere due to the loss of material copies or the condition of the records. In 2009, a journey began to restore, digitize, and recirculate the films that are now presented. ADF wishes to extend special thanks to Deepa Dhanraj, Arsenal, and BIOS Cinematheque for their support in realizing this screening. Curatorial text, Athens Design Forum.

YUGANTAR COLLECTIVE

Founded by Abha Bhaiya, Deepa Dhanraj, Meera Rao and Navroze Contractor in 1980, Yugantar made four pioneering films. Working collaboratively with existing or ensuing women’s groups, Yugantar forged novel filmmaking practices and political vocabularies that still resonate today. https://yugantar.film/

In Conversation with Deepa Dhanraj

The factory in Tobacco Embers is characterized by unbearing portals – transitional spaces that uniquely manifest to show how laborers coexist with parameters of space at the proxy of design. As a confining force, built structure mediates the livelihood of the female protagonists. The role of director and cinematographer as a conveyor of this mediation is paramount.

ADF founder Katerina Papanikolopoulos speaks to Director Deepa Dhanraj, one of the founders of the Yugantar Collective (Est. 1980), whose process and philosophy formed a methodology of collaborative and activistic filmmaking centered on working-class women’s voices. The following interview shares how the images and sounds of labor were transformed by the filmmakers into resistive resources meant to evoke change.

On the images of labor

DD: In Sudesha and in Tobacco Embers, it was very important to show the laboring bodies of the women – to show the actual labor of it. In Sudesha, for me, it was so much about what does it mean just to survive in that landscape? It is a ten hour walk to get fodder for those animals, even to bring water is backbreaking, even to eat rice, it takes you a half an hour of pounding to get just a handful of grain. It was fascinating that it was a movement from the Global South to talk about forests, to talk about ecology, how local communities nurture and protect, how they use resources although they do not exploit the resources. It is more like they are shepherding resources, conserving while they use. Later, that movement started what is now known as ecofeminism internationally. At the time, women were in the forefront. For them, it was survival – you cannot survive in that landscape as you need fuel and water. Once those elements disappear, it becomes a desert.

On gates and portals – the architecture of confinement

KP: When you were filming the gates and portals in Tobacco Embers, what did the collective seek to convey?

DD: The gate is very important because they get locked out. Even if you were a few minutes late, you would get locked out and you were not allowed in. The whole idea of the gate is not only that you get locked out, but you are locked in. There were stories of women who were breastfeeding their babies and they had to beg to go feed the child and come back. The shot of the door of the factory opening shows that inside it is just so dark, they are working in really horrible conditions. We got into this factory because the women of the movement convinced the owner. We had to finish that shoot in three hours. There were over ninety factories there, and he said, “You have three hours and that is it!” We had not seen the factory before, can you imagine? You just get in and you start.

KP: You can sense it. We approach the space alongside you, your vision guides us and we are simultaneously experiencing the built environment for the first time. When the women were sleeping inside the factory and their tools (basketry, wooden planks) were put to the side, how do you believe women transformed these spaces?

DD: About being locked in: you have to rest – and actually, I was very shocked because not only are you breathing the tobacco, but you are lying down on it. Your hair, your clothes, how can you sleep on piles of tobacco? For me, I think of it more as there is not even a space in the factory for them to spend ten minutes outside. They eat there, they sleep there, they even eat food right there. I asked a lot of questions about older women who worked in the factory. ‘What was their health like?’ as you cannot be exposed to that level of dust without serious problems.

On dress as protection

KP: Recurring scenes show the women’s use of the sari as a mask and a shield. How would you say their dress is transformed in terms of industry?

DD: They are wearing a sari, a six-yard fabric, which they wrap around themselves and around their head, and they make a mask out of it. It is from the same garment they are wearing, it is the extended part of the sari. You know, inside that factory you cannot breathe because the tobacco dust is so fine that it gets into everything – on your eyelashes, your hair. We could not stand it for more than five minutes as you had to go out. You want to throw up as it gets into your lungs. We had to clean the camera three times as the dust was so fine, it was like talcum powder falling onto the lens.

KP: The architecture of the factory did not seem to have any form of ventilation…

DD: There was no ventilation as the factory owners do not want to lose even five grams of tobacco. That is why – to keep it all in. You know what women have to do? When they first come to work in the factory, they are given tobacco for free..they can chew it as much as they want…because you have to get them addicted. The nicotine level in the body has to match that kind of nicotine exposure in the factory. That is why we could not stand it…after five minutes you feel nausea as you are swallowing the dust.

On the songs of labor

DD: We have work songs for everything in India. We have work songs for transplanting rice, songs vocalized for agricultural activities. The songs are a way to keep you going. There is a rhythm: not a rhythm of work, but a rhythm just to increase stamina and the feeling that you can do, say, another ten minutes – no? It is a method that they use and those songs are not really related to tobacco. The agricultural work songs are very linked to agriculture, but this song they were singing was more like womens’ folk songs, a working song.

On porcelain and the caste system

KP: The emphasis on the porcelain cups and the tea within Tobacco Embers…there is a shot of a child’s leg and the used porcelain cups.What was the meaning behind these sequences?

DD: The porcelain cups have a story actually. In India, we have a caste system, and the women who work in these factories are from the lower caste, the untouchable caste. There are certain tea shops where this caste group can go, run by Muslims. Traditionally, the untouchable community will not be served tea in metal (metal, brass, copper, silver, or steel). They will serve it in porcelain as it is a modern material that cannot be ‘polluted’ by the ‘touch’ of an untouchable. Now, of course, you have stainless steel which is a modern material, and everyone uses stainless steel, but the porcelain at the time was a neutral material that did not have that association. The cup and saucer were inherited from the colonial period. That scene is also about leisure. They need space… and it is something so beautiful to share tea, to share a moment that is not work. Drinking tea with your friends or the women you work with. For me, it was that kind of moment.

On the sound of one’s breath and the leaf as spout

KP: In Sudesha, the women used a leaf to make a spout for the water. Was it spontaneous?

DD: Yes, that is what they do. It was beautiful the first time I saw it. What we did is that we stayed with them the whole day. They go downhill and cross the river that is freezing with ice water. So, within eight hours, you go downhill, you cross this river, you climb up, then you collect the fodder, and then walk back up. You can see in that sequence when they are walking up with the fodder. I told the sound recording artist you have to get the sound of their breathing, as it is so hard walking up…the breath…during that whole time we were filming whatever they were doing and suddenly they stopped and drank water and were so beautiful.

On process

DD: We started each film with a conversation. This process meant that our Collective was in conversation with the women’s labor collectives. What stayed from the Yugantar project, at least for me in my film practice, is this idea of collaboration: of working with a collective. None of my films except Sudesha, are based around a single character, single individual, or one story. All my work even after that still has that quality of a larger group. They are films about ideas rather than about personal stories of one or two people. If you look at Tobacco Embers, it was made with women from those unions. Part of this process is deciding what you want to say in your story. What are the important points where you felt something happened? The women were very keen that the ‘night strike’ in Tobacco Embers was an important moment or in Sudesha, when the protagonist talked about how they would chase away the contractors. In each instance, we felt that the idea was then how to create a re-enactment. We had to do a re-enactment as we came after the event, once it was over. The interesting thing is that we did the re-enactment but we shot it like a documentary, we did not shoot it like fiction, so there is something weird about that. So the reenactments came out of these conversations about important moments in their fight that they felt had to be in the film, or else you could not tell their story…they were very proud of these actions. You know, at that time, we were all very young and I never went to film school so my thought was – you need a re-enactment? Let’s do it, there was no fear…we just felt very guided by the women.

Before Tobacco Embers, we took a room where the women stayed – it was like a favela, a slum. We were there for three months and women would come in and out. We would have conversations…they could not understand us: They kept saying, “What do you do all day, what do you do hanging around, is this a job?” As we had to wait until they came back from the factory at night, they were so curious, “What kind of life is that? You can sit here for three months and basically hear us talk…” Same process with Sudesha. We spent more than a month with her before we started shooting.

I think those long conversations, which were about why make the film and who is going to watch it, were formative in creating this loop: we came to the communities and then we were going to show it to other women workers in different parts of the country. This was a protest, an action, or a strike that they led and got them somewhere, it was a success story. This is how we used to start these conversations. And then of course there is also friendship. It is not all political; it is about families, problems they are facing…drunken husbands…children..managing on very little money. The whole relationship is more than work or a union story.

We would always show the rough cut, so we went back to the communities to share Tobacco Embers. There was a doctor who used to have a theater and he would show one film per day. We had to wait until the film was over at midnight to show our rough cuts. Over two-hundred women came to watch them and we had to show them many, many times as it was not enough to see them once. We had conversations about what they liked, what they didn’t like, did they want to change something or not…and then we wrote the narration. The narration we wrote stemmed from my notes. In the conversations we had prior to filming, I had made notes of exactly what they had said – I would remind them,“This is what you said, can we put this in?” Then, we recorded it in their voices, and one woman would speak it and then forty women on the side would say, “No no no, you have it wrong… change this word…change that line..” It was quite fantastic!

On the role of activism

DD: I was very interested in bridging the time gap. After 40 years, what do young people make of it and what do women workers of today make of it? One woman told me after watching Tobacco Embers, “You know, this is a very traditional form of union work…traditional meaning: the meetings, the conversations, it is very ‘old school’...”

In Tobacco Embers I am most proud of that last scene because that’s what it was. It was three shots, which we did not cut, and the camera followed the women talking, arguing, and fighting. It may not be very ‘coherent,’ they may not come up with some grand plan, but that is how the meetings were. And it is all to end the film to say it is a process…it is a process of negotiation, argument, coming to consensus. It is very democratic how they work. Everybody has a chance to speak and argue. So, for me, that is very beautiful. You see them at work, that is how they do politics…. and you would not have that in a traditional male left trade union as they are very hierarchical. There it is formal – there is a committee, and ways of doing things. I mean look at these women, it is a very equal space. When we were editing it, my editor said, “This sequence does not make any sense…it is not ending anywhere.” I said, “That is the point… to see them, that is what they do every evening. When they have to plan a strategy or something, that is how it is done: somebody comes up with an idea, somebody says, ‘That is bullshit,’ somebody says, ‘try this, let’s try that… I do not think this or that will work’. It is great!

KP: In Sudesha, within the Chipko Movement, many male figures held key roles although the females were the stronger core leaders…what happens in those cases when it is a male and female in the same discussion, how was the balance different?

DD: In the Chipko Movement, the leadership was completely male although the men needed the women as they were the ones fighting on the ground. Firstly, to organize women in the hills is very difficult, as every village is far apart. Even for women to come together for a meeting is very difficult, physically even. Once they had some success in stopping the felling of trees beyond a point, the movement disappeared. One of the tragic things that happened with Chipko is that all they wanted was access to the forest as guardians…they would take only what they needed. When the ecology movement started it backfired on the local people. What happened then is that the Forest Department closed access to everyone. So, this whole eco-feminism, ecology movement, and conversation movement did not work for people… the forest department took over and then kicked everyone out. The timber traders were not totally forced out as they would have auctions – although, the fight was for local people to continue to live in that environment, and for that, they needed the forest…they lost that war.

That is where I feel the eco-feminist movement got it wrong…they were looking at putting the forest before people and all the people were saying is let us be the guardians of the space…for hundreds of years we have protected this space, give us back this authority. Once you say the forest needs to be protected and nothing is taken out of it, then people are nowhere, no?

On the present

DD: From that time to now, there has been so much damage as they started dynamiting to build power stations and have diverted water to the cities. So now in fact you have ghost villages…even to farm there is not enough water. Sudesha Devi is alive – she is in her late eighties. She is in the village although it is a tough life.