THE SENSORIAL MASS.

A photographic archive of Blegen’s Excavations at Prosymna

01

“The pursuit of forms is only a pursuit of time, but if there are no stable forms, there are no forms at all.”¹—Paul Virilio, The Aesthetics of Disappearance

02

03

In the wake of archaeological photographic images, we may begin to decipher Paul Virilio’s conception of the sensorial mass: how the stabilized form of an excavated artifact becomes eternalized within the cage of a photograph. If photography functions as a penetrative method to assert an influence of cementation, then the decisions that remain unspoken—placement, framing, repetition—are prolonged in time. In this stillness, a series of anomalies accumulate.

Virilio’s Aesthetics of Disappearance offers a framework through which we may understand these tensions, borne as a new condition of visibility at the boundary-line of image. The artifact becomes a form of anatomical digestion through the evolution of study, photography, and indexation. What disappears in the transmission is not the object itself, but its circumference: its prior life as a sensorial mass embodied in all dimensions. In the act of making matter concrete, there is a haunting of disappearance, a lucidity that encompasses the backdrop.

The 1926–1928 excavations at Prosymna in the Argolid, led by Carl Blegen, serve as a singular instance of how archaeological findings become fossilized through the photographic mirror. While not the first Mycenaean site to be photographed, Prosymna is among the earliest to integrate stratigraphic excavation, typological ceramic analysis, and rigorous photographic documentation as a unified scholarly method. Yet, embedded within this visual record is the labor of women who shaped the evidentiary logic of the archive. In the slender preface to Prosymna: The Helladic Settlement and Grave Circle (1937), Blegen briefly acknowledges the contributions of Mrs. Blegen, Mrs. B. H. Hill, Miss Marion Rawson, and Mrs. R. K. Hack, who cleaned, arranged, supervised the photography, and captioned the artifacts. This series of events ensured the longevity of the artifacts as they entered the medium of stability afforded through the photographic record.

Virilio, quoting Proust on the Marquise de Sévigné, reminds us: “She does not present things in a logical, causal order, she first presents the illusion that strikes us.”² This illusion becomes, in many cases, the enthroned artifact as it is removed from the grave, stilled, and reanimated in the breath of photographic life.

04

05

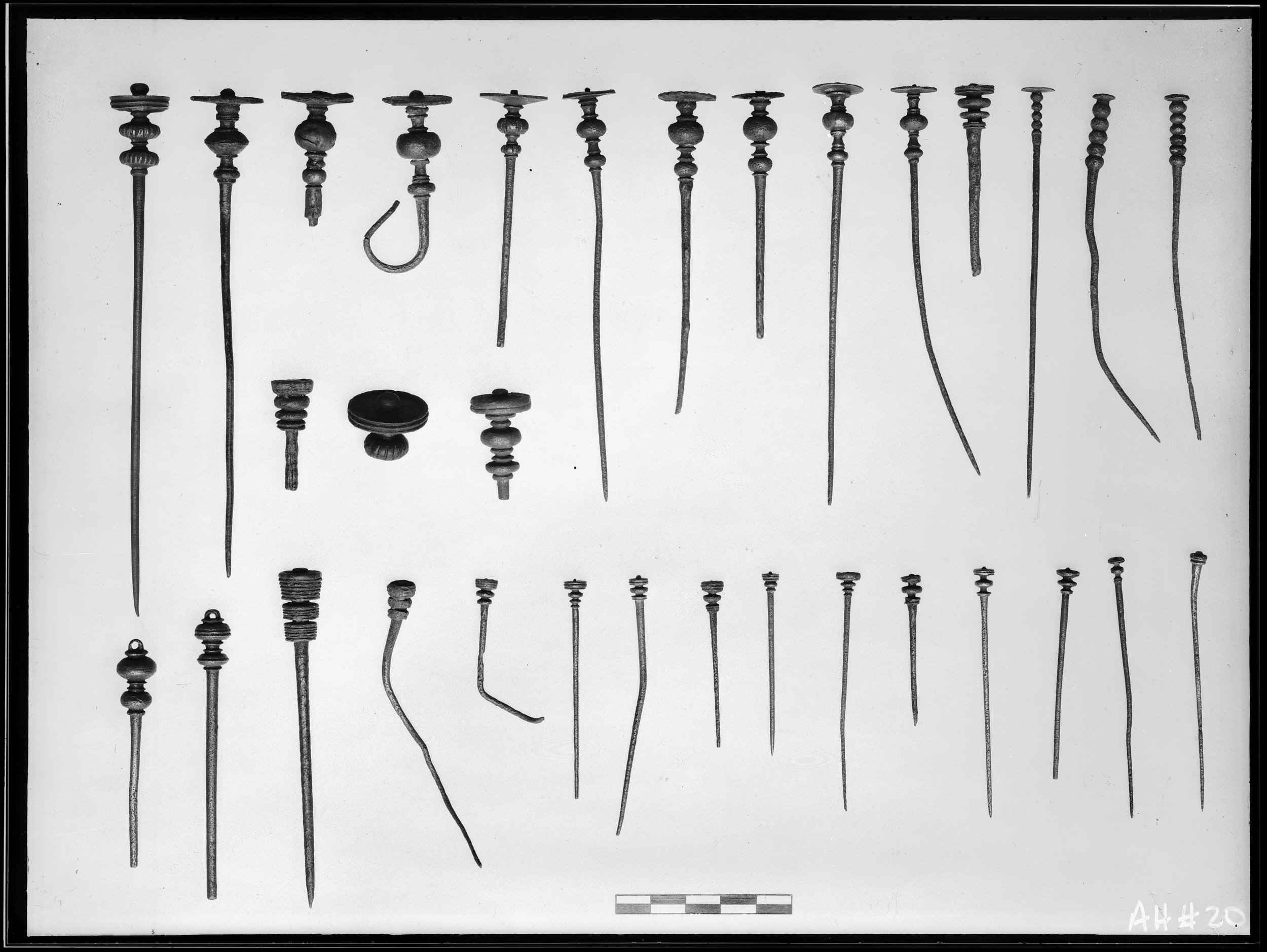

The aesthetic patronage of these women becomes evident in the creation of a visual methodology. Artifacts are aroused through a rhythm of repetition or intended isolation; “straight” iron pins from the terrace of the Early Shrine form a parade of individuation even within their classified order. Shell specimens are countered by the sharp arrowheads placed below them – a dichotomy of softened, natural forms placed in the shadow of a violent foundation. A shell necklace is staged in the line of an imaginary neck of the bereaved, with the bifurcated edges rendered so delicately that their context is overwritten (Shell necklace, from grave XX). Within imagery of the Statuette of Horus (Egyptian, 26th Dynasty), the representation of the airborne artifact makes us imagine the seat which no longer holds the body of Horus, her contour suggesting such an appendage. The split-frame perspective of frontal and side views produces an exact dualism – also evident in the depiction of the tripodal ceramic chair from Tomb WI, enacting a form of motion in the speed of perspectival transition.

Influenced by Napoleon’s dictum, Virilio observes: “To magnetize masses, you must above all talk to their eyes.”³ The photographic archive of Blegen’s excavations, especially as preserved and digitized with care by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, performs a similar function. The augmented choruses of looking produce a magnetism structured by the vestiges of disappearance itself.

With gratitude to the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Archives, Archaeological Photographic Collection, for granting permission to use the selected images (© ASCSA) and the Photographic Archive of the Hellenic National Archaeological Museum, Athens (©Hellenic Ministry of Culture – Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development).

Text written by Katerína Papanikolopoulos.

06

07

Notes

Paul Virilio, The Aesthetics of Disappearance, trans. Philip Beitchman (New York: Semiotext(e), 1991), 17.

Virilio, Aesthetics of Disappearance, 35.

Ibid., 54.

Image captions

01 Straight pins. From terrace of Early Shrine.

02 Shell; necklace. From grave XX.

03 Two arrowheads; shell specimen. Chamber, tomb XXVI. LH III.

04 Female statuette; Minoan style. Tomb LI. Associated with late Helladic III pottery.

05 "Palace style" sherd. Tomb VII.

06 Statuette of Horus; both arms missing; from "Shaft Grave". Egyptian.26th Dynasty.

07 Chair. Tomb WI. LH.