The Spherical Axis: Escombros and La Forma De Memoria by Javier Aravena Costa

Escombros © Javier Aravena Costa

“Revisiting the figure of the pirquinero allowed me to explore a specific form of resistance—one that continues to express itself through exclusion.”

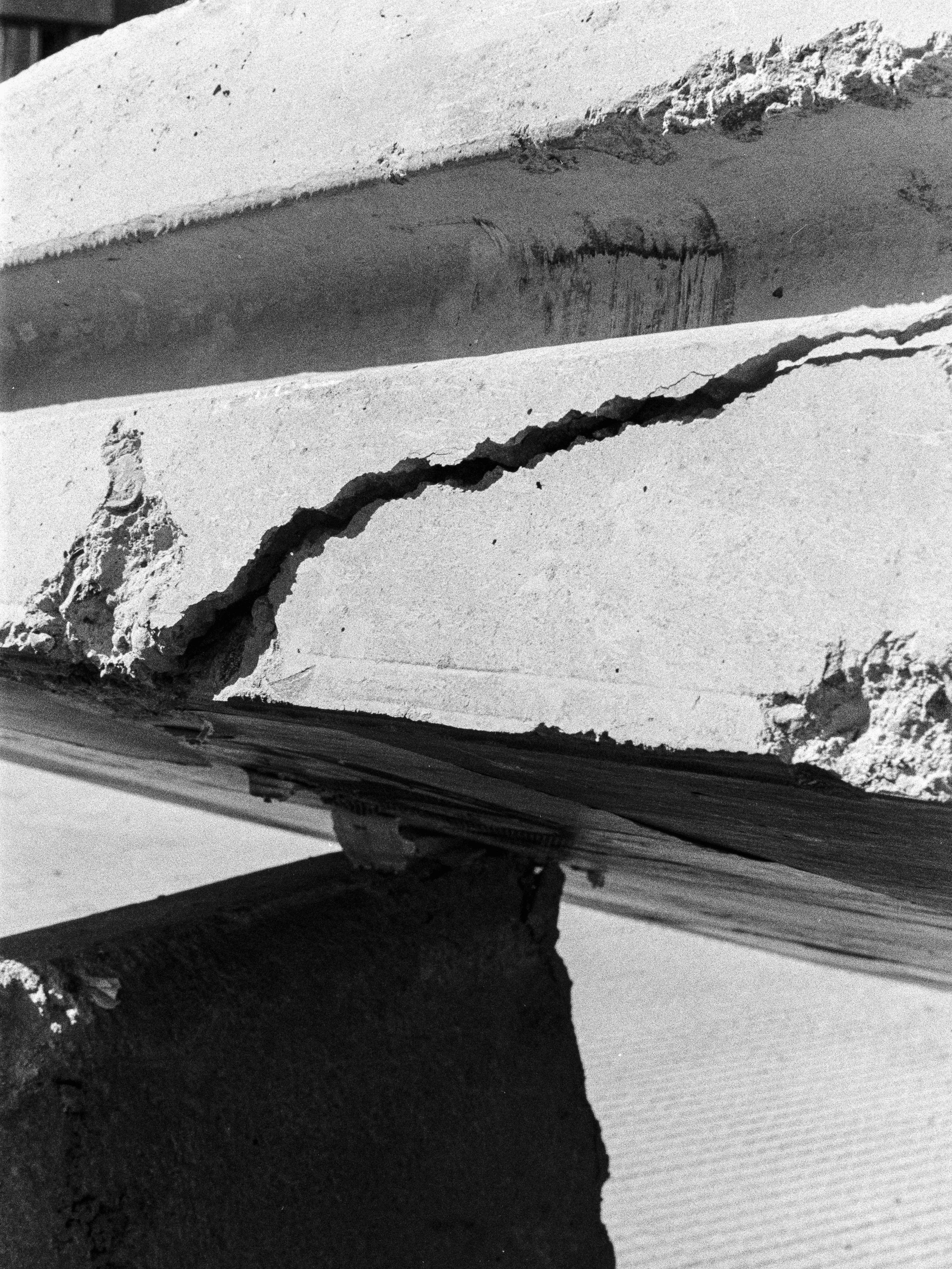

Athens Design Forum presents Escombros and La Forma De Memoria by Chilean researcher and photographer Javier Aravena Costa. When extraction is articulated as a symptom of industrial annunciation, architectural permanence is dismantled. In the absorption of a geography’s lack or abundance, Costa deciphers the conscious alternation of landscape and how ‘new contexts of resistance’ inform the forging of territorial identity.

Within Escombros (debris), the pirquinero (small-scale miner) embodies a legacy of pre-Hispanic mining in northern Chile. Costa mediates on the weight of language:

“With Escombros, I began by translating Quechua words—this allowed me to locate the origins of a technique through language, its history, and symbolic weight. The aim is to reframe the technique of the pirquinero, reclaiming its history and meaning through the act of chiseling and deconstructing concrete—particularly in resistance to the neoliberal model that emerged following the social uprising of October 18, 2019.”

There is an indigenous, linguistic threshold that permeates sites of inhabitation—evidenced in the timely neglect depicted within La Forma De Memoria, which focuses on traditional building techniques such as adobe and quincha (timber framework with mud). Centered in Chile’s norte chico, these architectures, now fading, are gradually reintegrating into the earth they came from.

Seen spherically on a unified axis, Costa’s photographic medium engenders a new potentiality and universal paradigm: what is abstracted, near dissolution, is set free or at least back to the very fundamental unit of life where it once sprung from. A conversation in dialogue with the artist follows.

The following interview has been translated to English.

Escombros © Javier Aravena Costa

Escombros © Javier Aravena Costa

From Quechua:

Pircca = Wall

Pircani = To build a wall

Vinachani pircaccta = To raise the wall further

Pircay camayok = Mason

How does language play a role in your broader practice, particularly in relation to Indigenous origins?

I begin Escombros with this linguistic reference to highlight the architectural concepts embedded in Indigenous knowledge—knowledge from peoples who inhabited this land long before us. Their construction techniques are the foundation that guided the conceptual framing of Escombros.

"In Chilean history, the pirquinero is part of the working class and has preserved the fundamental concepts of mining. Their technique is a legacy of a pre-Hispanic mining tradition based on knowledge of the land and its resources—understanding the various layers of material that could be extracted and selected from rock formations."

What is the relationship between the human body and concrete as medium? Where do fractures, anomalies, or synergies emerge?

Escombros © Javier Aravena Costa

My first shift in the editorial direction came when I witnessed the pirquineros and the act of striking concrete. This intrinsic gesture carries many layers of meaning. Two moments stood out to me: first, the channeling of a contained rage, enacted through the striking of a surface. Second, the outcome of that gesture—the forms of these fragments, ranging from abstract to specific. These smaller rocks were moved to the frontlines, serving as tools to counter the police’s advance.

The next step involved understanding this material as a resource for building other contexts. Here, cobblestones come into play—concrete structures recontextualized as tools of resistance, used to build walls and create spaces of containment. Regardless of scale, they reinforced a collective action.

The second thread of the project is concerned with the displacement of these elements and how they interact with geography—allowing for a reinterpretation of the landscape through an assigned discourse. This thread connects to architecture and objects through the lens of fracture. I chose not to document the protests as they unfolded, but rather to work afterward. At dawn, I would walk through the spaces where the largest quantities of rock had been gathered by the pirquineros—Ramón Corvalán’s intersection with Alameda, for instance, and the monument of the police.

Escombros © Javier Aravena Costa

The movement of these fragments and their interaction with the site form the crux of the project. This series of images reflects how their production, transformed into a political and social act, has redefined Santiago’s central landscape in an active, enduring way.

How have forms of extraction evolved or devolved in contemporary praxis? What led you to revisit pre-Hispanic mining traditions, and what may this knowledge forge for future generations?

I believe that in order to situate oneself in the present, one must understand the past. To position yourself in a territory’s timeline is to not only take part in its history, but to help shape its identity.

Revisiting the figure of the pirquinero became the thread running through my research. It allowed me to explore a specific form of resistance—one that continues to express itself through exclusion. Throughout Chile’s mining development, the pirquinero has been marginalized—often left unrecognized as integral to mining itself. Coming from lower social strata, they’ve historically been diminished, yet their legacy is deeply tied to the territory’s history and identity.

Meanwhile, extraction and industrialization progress at a pace that ignores these more human, territorial dimensions. The distance between the world of large-scale mining and the pirquinero only becomes visible depending on the lens one adopts.

With Escombros, I position myself and invite reflection. I believe that is the true contribution: to understand history, make it one's own, and from that comprehension, articulate a position.

Escombros © Javier Aravena Costa

How did you prepare your research process for Escombros?

The project begins with an understanding of the territory of Plaza Dignidad through its transit, reading the space via markers that speak to its fragmentation. Initially, the perspective was tied to a sculptural lens, focusing on the residue left in the aftermath of upheaval. My visits to Plaza Dignidad happened within the context and timeframe of the protest, aiming to identify where the most significant changes were concentrated. This phase is crucial to building the language I would later develop.

The first act of recognition, in some sense, I interpret as a tourist’s gaze, within the photographic language one begins to construct. I find this part the most difficult to resolve; in documentary practice, it’s easy to be swept up by events that are already compelling in themselves. Finding clarity in that approach was a concrete step. My experience is rooted in specific moments that, while part of the whole, also transcend the immediate context.

Cizalla Editions (2020), Escombros.

Begin to define the politics of this type of project, considering how it situates itself more broadly as an act of resistance to established systems.

I believe it’s important to understand that projects like this one transcend specific events. The political moment in Chile in 2019 represented a force and collective empowerment that was impossible not to inhabit. Time hasn’t validated our hopes; the frustration born of many causes became the footnote to the uprising we experienced. The relevance of such projects is affirmed through the identification they foster—how far they travel, how widely they resonate, depends on that as well. What’s key is to inhabit the possibilities of language and to seek a mode of representation that isn’t too direct. That distinction, I think, is fundamental.

How do architectural space and design principles infiltrate the foundation of your work?

To understand how architecture relates to my projects, it’s essential to reflect on how lived experiences in space can inform and shape an artistic proposal. At university, a professor often emphasized the need to maintain clear direction—defining a research area and integrating nuances that would guide creative process without losing focus.

That idea stayed with me, and certain pivotal encounters with territory shaped my connection to architectural space. One of them involved a project on an industrial park where I worked for a time. Returning to that site allowed me to explore different ways of interpreting space, especially in relation to large structures and their residual zones.

Over time, my work has braided itself into mineral, geological, political, and geographic threads—ultimately circling back to architecture in Escombros and La Memoria de la Forma. This trajectory also led me to recognize the artist book as the representational tool that best fits my process. As the first visual results emerge, the project begins to take shape, which then initiates the design and editing phase. For me, it’s essential to build a dialogue through the images—one that not only accompanies but actively embodies the conceptual framework. Design, in this sense, is what allows me to link and articulate those worlds.

LA MEMORIA DE LA FORMA

La Memoria de la Forma © Javier Aravena Costa

La Memoria de la Forma © Javier Aravena Costa

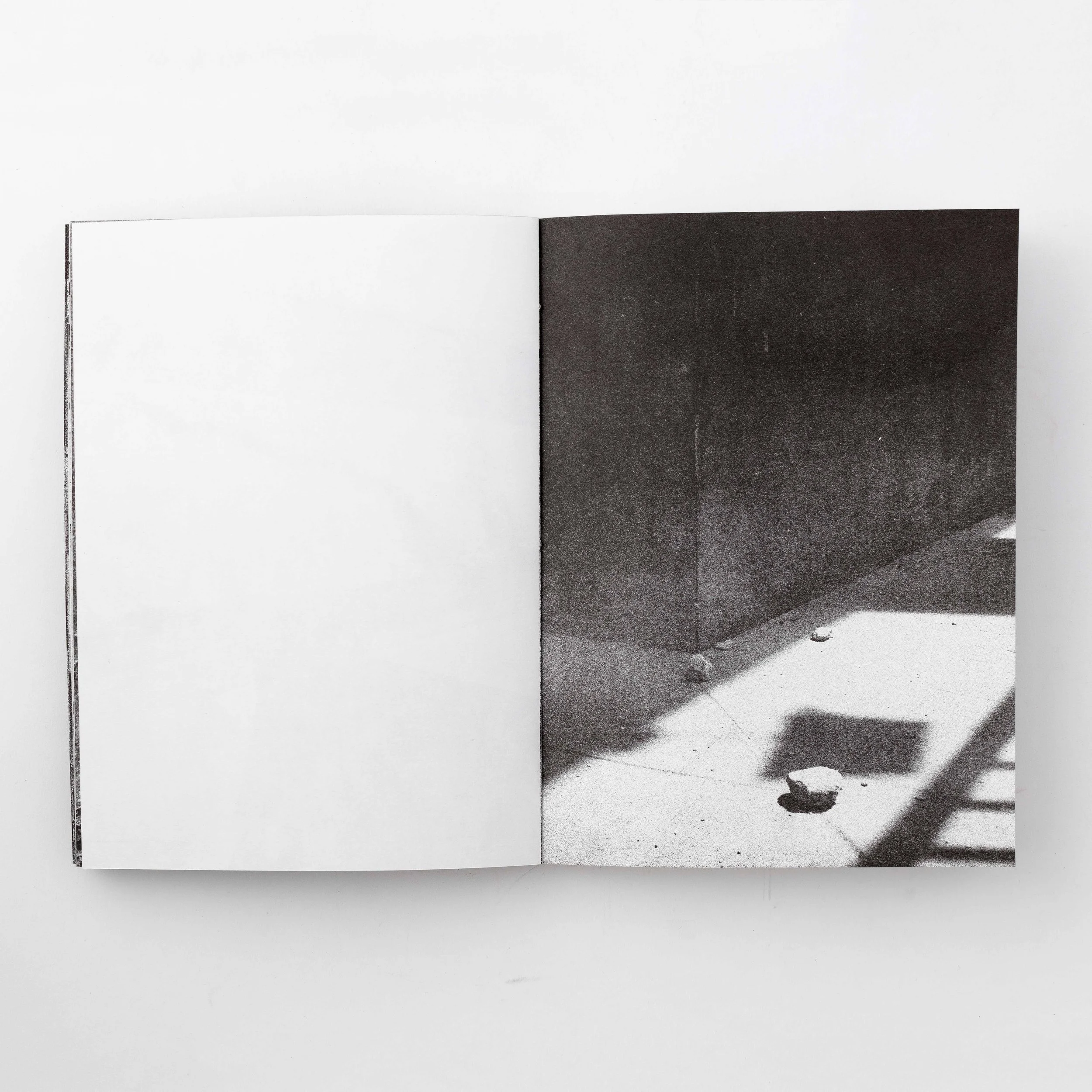

It’s important to introduce a key concept that has shaped my recent projects. While researching Escombros, I came across the work of Argentine anthropologist Gastón Gordillo, who offers a particular view of what we call "ruins." For Gordillo, a ruin is what time does to a structure—when preserved, it becomes heritage, a trace that testifies to both a building and the society that lived it.

Yet Gordillo also considers places that don’t fit the classical definition of ruin, focusing on architectures that maintain a living dialogue with their surroundings. That idea became central to my work.

With Escombros, I began by translating Quechua words—this allowed me to locate the origins of a technique through language, its history, and symbolic weight. Revisiting the projects over time has revealed multiple threads that support their conceptual base: stone, history, identity, territory, politics, geography, and architecture. Reconnecting with these ideas continuously opens new pathways for inquiry.

Escombros revealed a deeper seam of research. I began traveling to the northern regions where pirquineros work, which initiated my journey through Chile’s "norte chico" and became the footnote to La Memoria de la Forma, my current project.

La Memoria de la Forma © Javier Aravena Costa

La Memoria de la Forma © Javier Aravena Costa

On structural weight. Describe the adobe house construction methodology and the role of the photographic medium in transmitting this.

La Memoria de la Forma explores traditional construction techniques from Chile’s "norte chico." For centuries, adobe and quincha were the foundation of local architecture. Both techniques are rooted in the use of local materials: quincha is a timber framework covered in mud, straw, and plant fibers; adobe uses a similar mix, formed into bricks and sun-dried.

Remnants of these structures still populate the landscape, speaking of a past that endures in the present. This reflection is the origin of the project, guiding its editorial and research direction. These buildings are also sculptures of time—forms that embody a material memory.

The goal is to preserve, through image, the time embedded in a landscape and its architecture—revealing how time has shaped these forms, their construction logic, their nature, and their current state. These architectures, now fading, are reintegrating into the earth they came from. Their condition as escombros (debris) affirms their existence and identity—their story is told by time, illustrating the continuity of a form.

“My projects approach landscape through movement. The goal is not a fixed model, but a trajectory—a strategy to understand geography, politics, and material through territory. Each project begins with an exploratory walk through a predetermined area, often in zones of mixed use or between urban and natural environments. In this photographic research, the landscape is not understood as a whole, but as a crossing between one place and another, shaped by potential traces of identification and transformation into visual signs.”

Describe the challenges of this position within an ecosystem, and how your perspective has been shaped through photography as an access medium—a method to mitigate landscapes in flux.

For me, creative work stems from personal history. Since childhood, I’ve been deeply attuned to my experience of landscape—its movement, the memory of moments lived, repetition, family experiences... an endless series of unique impressions. For me, the channel for those memories is photography.

It allows me to revisit the spaces I once inhabited and to perceive their problems beyond memory. My development is rooted in experience; each project occupies a place in my memory. I feel that “tracking,” as your question suggests, is a process that moves between two poles: creation and remembrance. The landscape helps me see beyond memory—that’s where my work begins.

My projects don’t arise from a current problem in need of urgent resolution. Rather, my work grows from a longstanding relationship with landscape—recognizing it as a field for development, in line with my ongoing research. It is from this place that my work engages political, geographic, and geological dimensions.

La Memoria de la Forma © Javier Aravena Costa

La Memoria de la Forma © Javier Aravena Costa

La Memoria de la Forma © Javier Aravena Costa

La Memoria de la Forma © Javier Aravena Costa