THE LANTERN OF BERAT, XHANFISE KEKO

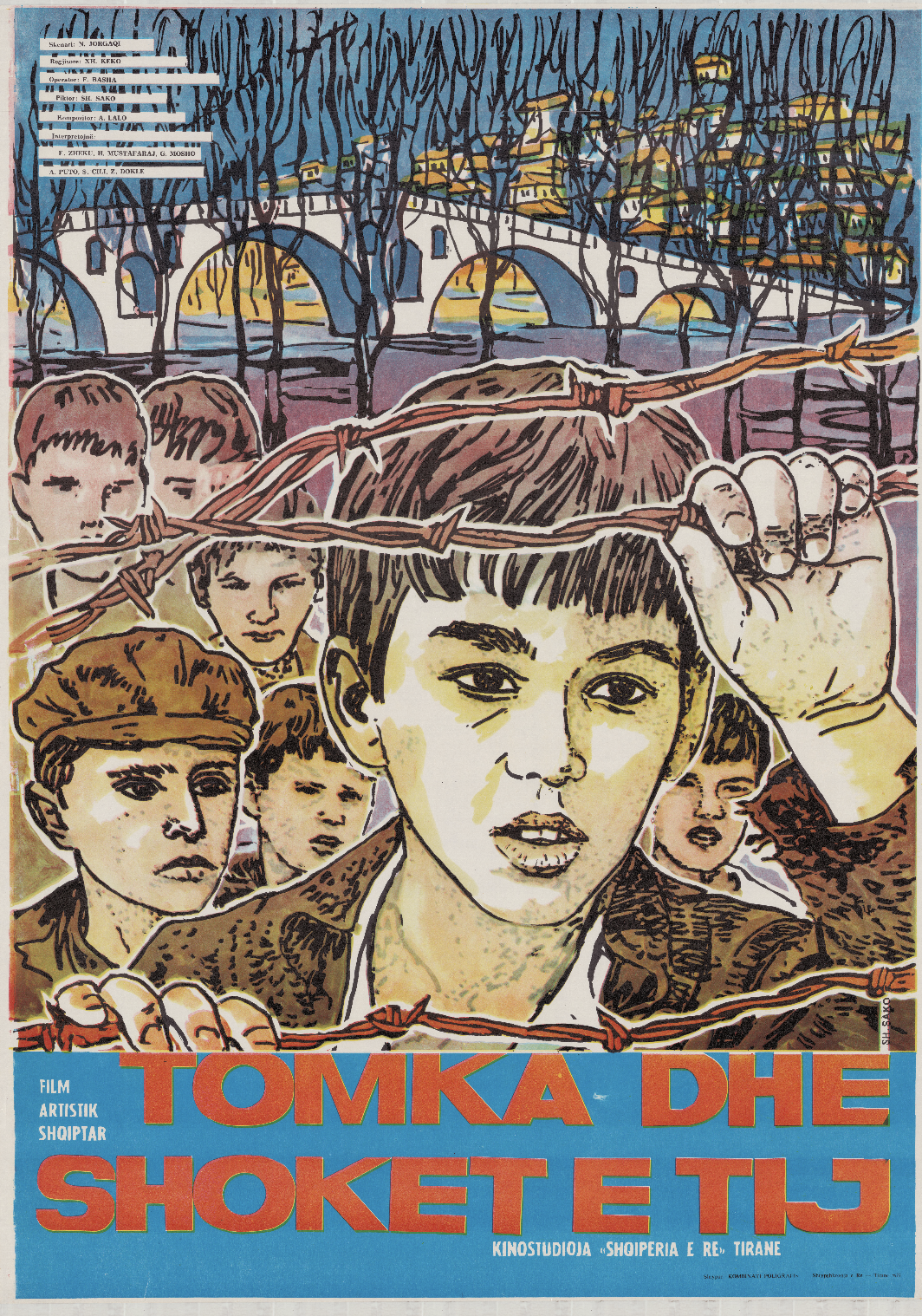

Original Poster for Tomka Dhe Shokët e Tij (1977) by Shyqyri Sako © The Albanian National Film Archive (AQSHF)

In the closing sequence of Tomka and His Friends (1977), the Albanian village of Berat is deciphered solely in the night through the Ottoman windows, shown through the ignition of lanterns that come to frame the city's awakening. The legacy of Albania’s renowned director Xhanfise Keko rests on the shoulders of this ending. Athens Design Forum invites Genc Permeti of Ska-Ndal Productions—producer, screenwriter, and advocate of Albanian cinema—for an exclusive interview in homage to featuring Tomka and His Friends (1977) by Xhanfise Keko for Milan Design Week 2025 at Dropcity Center for Architecture and Design. The film’s enduring language and intentional engagements with architectural discourse are embodied in Keko’s reflection, “It is no coincidence that resistance unfolds in the few places collectively owned by the city's inhabitants.” Permeti’s interview is animated with excerpts from Keko’s memoir “The Days of My Life” (2007), published in English for the first time with the guidance of Keko’s son, film director Ilir Keko. Chronicling an artistic journey over 79 years, the shared conversation solidifies narratives that shaped a filmic cultural revolution beyond Albania’s borders.

ATHENS DESIGN FORUM: Architecture and place are central to the film’s narrative. How did the narrative evolve to center the playground and barber shops as sites of resistance?

GENC PERMETI: The author defines the geography of the story’s development within the parameters of city, landscape, streets, and houses; what ties the geography of the story’s development is the football field, which becomes the magnetic center of these children’s universe. So, when the Nazi army takes away this space, the children become part of the consequences of occupation. Everyone, in one way or another, becomes part of the World War, and the children are the ones who emotionally experience it with a particular hatred. Their universe has just been stolen. But will they give up the field that is part of their lives?

Barbershops, throughout the last century, have been considered social spaces where everything was discussed—politics, sports, war, family, etc. Therefore, like an agora of public discourse, they could not remain outside the positioning during the war, where everyone had to decide whether they were for or against the occupation. Fortunately, in the film Tomka and His Friends, this agora is positioned on the right side of history, symbolizing our country’s participation in the anti-fascist coalition. We also see this element in European and American films. Barber shops are environments that creators like Hal Hashbi and Spike Lee have used as settings in developing narratives where human nature is expressed truthfully in approval or opposition to authorities.

<> “Barbershops, throughout the last century, have been considered social spaces where everything was discussed—politics, sports, war, family, etc. Therefore, like an agora of public discourse, they could not remain outside the positioning during the war, where everyone had to decide whether they were for or against the occupation.” ~ Genc Permeti

XHANFISE KEKO, Excerpt from “The Days of My Life” (2007): Berat is a city of narrow alleys, with houses built closely together, leaving few communal spaces for its residents. The only shared areas were the fields by the river, where the city's children gathered to play, and the central bazaar, where adults met to exchange goods and interact. It is no coincidence that resistance unfolds in the few places collectively owned by the city's inhabitants. Focusing on the field, it was entirely the children's domain until the day the Germans entered the city and set up their military camp there overnight. The next morning, when the children arrived to play as usual, they found the field occupied. This moment of disappointment sparked their desire to challenge the occupiers. They decided to play right in front of the camp entrance, singing and dancing in full view of the German soldiers.

However, the Germans reacted aggressively, unleashing a dog to scare them away or beating them to drive them off. This hostility quickly transformed into hatred, which the resistance forces skillfully harnessed. The children were mobilized to count the weapons inside the camp, locate the tunnel exit, and even poison the guard dog—since the ultimate goal was to blow up the German encampment. And they succeeded, thanks to the children. Looking back today, I believe that from a dramatic perspective, this human conflict between children and occupiers was masterfully portrayed and resolved in the film—through the script, direction, cinematography, atmosphere, the children's performances, and the music.

Ultimately, the struggle over the field is what sustains the narrative of Tomka and His Friends. Meanwhile, the plans of the adult resistance members unfold in the city center, where clubs, restaurants, shops, barbershops, and the bazaar are clustered together. This reflects historical reality. The adults involved in the resistance used public spaces to avoid attracting enemy suspicion while orchestrating their plans. A café or a restaurant could have been chosen, but we decided on a barbershop—simply because it was not only centrally located but also less crowded, offering a more discreet environment for discussion and planning.

ATHENS DESIGN FORUM: The film employs a unique montage of communication landscapes between elders and children – transforming balconies, staircases, and courtyards into communal rather than isolating spaces. Could you describe the cinematographic techniques used to achieve this effect?

Cityscape of Berat © The Albanian National Film Archive (AQSHF)

GENC PERMETI: The city of Berat, or as chroniclers call it, "the city of a thousand windows," imposes its structure on the distinctive construction style around the castle, where buildings have an almost human-scale relationship. The windows facing each other, and the narrow cobblestone streets winding through them, create a mystical image but also a physiognomy of a shared habitat where men after work, women, the elderly, and children use these spaces as common areas for creating narratives ranging from the smallest to the largest, discussing everything from the weather affecting the arthritis of the elderly to conspiracy theories about America’s entry into World War II. The balconies, courtyards, windows, and streets serve as an accessible set that imposes itself with its verticality, inspiring the author to bring Tomka’s story to life through a game of vertical lines and horizontal movements of characters. Feeling this advantage, the author was able to use various angles to provide a rich visual experience that aligns with the dynamics of the story.

Characters within these buildings operate on three architectural planes: the basement, the ground floor occupied by adults, and the second floor occupied by children. The author masterfully penetrated these locations, using them in favor of the characters and her stylistic approach with finesse. In this spirit, she achieved a successful union of the above images with a sound that corresponds to the clash of buildings, the claustrophobia of the alleys, and the dramatic tension of the characters.

Xhanfise Keko, Faruk Basha | Behind the Scenes of Tomka Dhe Shokët e Tij (1977) © The Albanian National Film Archive (AQSHF)

ATHENS DESIGN FORUM: How would you characterize the lasting impact of Xhanfise Keko’s work on Albanian and world cinema? What were the conditions in which she was working and the effects of censorship and the evolution of her films thereafter?

GENC PERMETI: Childhood is the central motif of Xhanfise Keko’s work. Seen as a genre that authorities did not scrutinize with an ideological lens, the author succeeded in telling stories that resonate with all audiences. Childhood is the most sincere part of everyone, and with her dedication, the author managed to penetrate the world of children, communicate with them, gain their trust, and convey their desires, dreams, adventures, sadness, and joy through film. Even today, 50 years later, these stories remain organic for everyone. Through Keko’s films, anyone can identify with a piece of childhood, with all its colors that were given to us. Tomka and His Friends is a milestone in Albanian cinema for the impact it had on an entire generation. A large part of the works that stand the test of time are said to be products of the generation in which they were created, while Tomka had an impact that defined an entire generation. Not by chance, after the film's premiere, many children were baptized with the name "Tomka." The fact that Tomka now enjoys a second, highly successful international life with growing interest shows that the success of this work, when it was made, was not a coincidence of its time but a result of the authentic depiction of the universe of childhood, which functions without boundaries of continents, cultures, or languages, but with the desires and dreams of childhood. The treatment of the loss of innocence through the harshness of the Nazi occupation, which in some ways aligns with the metaphor of social injustice, emotionally accompanies the audience for a long time after watching this film.

ILIR KEKO: While she studied in Moscow in the early 1950s as a film editor, the greatest influence on her filmmaking came from Italian cinema. Fortunately, many Italian films were shown in Albania between the 1950s and 1970s, making it inevitable that she would be influenced by great Italian directors such as Visconti, Rossellini, De Sica, Fellini, Antonioni, Pasolini, and others – the naturalism and spontaneity that characterize Italian neorealism are evident throughout her work.

ATHENS DESIGN FORUM: Keko’s films demonstrate a deep sensitivity toward child actors. How did she cultivate their performances and what specific techniques or approaches did she use to ensure their authenticity on screen?

GENC PERMETI: Xhanfise Keko’s work is characterized by its stylistic unity, the truthfulness of the stories she constructs, the diversity of shooting sets, and the organic connection between professional actors and child actors. Through extensive casting work, the author lived with the characters, creating a prototype of them in her subconscious and attempting to project it onto the children who fit the characters’ parameters. But this was just the beginning of the process. She then discovered the children’s inner world, enriching the characters with the truths of the child actors who, by the end of the preparatory process, no longer acted but became themselves. In some cases, the children’s own narratives became parts of the scripts, as in the case of the film When a Film Was Shot. Making films with children and animals has always been seen as a challenge for directors, and in the case of Tomka, both challenges are present. In order to create a complete work, Xhanfise Keko transformed into a true mother for the children, providing them the comfort only a mother can offer, not allowing them to feel insecure and instead, to see the filming process as their own playtime. This was the key to the success of Xhanfise Keko’s work, bringing the children’s natural behavior toward the story and guiding them with the camera.

<> “She then discovered the children’s inner world, enriching the characters with the truths of the child actors who, by the end of the preparatory process, no longer acted but became themselves.” ~ Genc Permeti

ATHENS DESIGN FORUM: In what ways did Keko communicate her vision to her creative collaborators? How did she guide the composer, screenwriter, and cinematographer to align with her cinematic language?

GENC PERMETI: Since the city’s landscape imposed a stylistic stance towards black and white, the interiors were also conceived with a clean graphic approach. With her stoicism, the author did a long preparatory and research process studying the ethnographic elements of the Berat region and the use of props that were in coherence with the period of World War II. The collaboration between the author, the director of photography, the scenographer, and the prop master was key to the success in creating an atmosphere true to the director’s vision, which allowed her to transmit to the audience a story that we can all become a part of.

XHANFISE KEKO, Excerpt from“The Days of My Life” (2007): I was fortunate to already know all my collaborators on this film, and I had worked with most of them before. This gave me confidence. I had previously worked with the writer Nasho Jorgaqi on the 1973 film Mimoza Llastica, and our collaboration as director and screenwriter had proven fruitful…He frequently visited the set in Berat, which allowed us to make last-minute refinements to crucial scenes before shooting. I had never worked with the production designer, Shyqëri Sako, before, but I was familiar with his work from other films. He was and remains one of the best production designers in Albanian cinema, and I consider myself lucky to have collaborated with him. Looking back, I believe Berat is a city that instantly captivates a painter. Its architecture, its vertical layout stretching from the ground to the castle atop the mountain, the stark contrast between the white stone houses and the black of their windows and doors, the narrow alleys, and the tightly clustered homes—these elements inevitably inspire an artist to bring its beauty to the screen. With cinematographer Faruk Basha, he was highly skilled with the camera and, since he was filming child actors, he made sure to keep the camera nearly invisible to them so they wouldn’t become self-conscious. As for composer Aleksandër Lalo, I am reminded of one of the film’s most memorable sequences—the song-and-dance performance by the children in front of the German camp. The day we filmed that scene remains special to me. But it wasn’t just that day—the preparations had started long before the moment Lalo arrived in Berat. Unlike anyone else before him, he had decided to spend his entire vacation on set. I greatly respected him—not just for his talent, but for his integrity when he gave his word. I remember that he once sent me a letter from Kukës, where he had been working for years, after reading the script: "Xhana! I’m optimistic and believe we’re going to make a beautiful film," he wrote in that letter, which reached me in early April 1977.

Thanks to his warm and engaging personality, Sandri (the composer) quickly bonded with the children. Sometimes with an accordion slung over his shoulder, other times seated at the piano in the Palace of Culture, he would invite the children to listen to excerpts from the film’s score. The only piece left unfinished was the song for the dance sequence. Feeling relieved that, at last, I was working with a composer I wouldn’t have to chase down to complete the music, I suddenly realized that the song still had no lyrics. I ran to Sandri and asked him about it. He shrugged, rubbed his temples—his usual habit—and laughed. "I don’t have any lyrics," he admitted. Then, almost immediately, he added: "Xhana, please don’t worry—I’ll figure it out." It was maddening! So absorbed was Sandri in crafting the melody for this challenging sequence that he had completely forgotten about the lyrics. To escape my questioning, he quickly called over the children. In an instant, they gathered around him in his workspace. I followed close behind. Sandri sat at the piano and played them the melody. Then, he asked what they thought. Seizing on their enthusiasm, he encouraged them to try writing the lyrics themselves. I stood back and watched, saying nothing. For more than two hours that day, the children worked around Sandri with incredible seriousness—each contributing a line, revising, adding, and removing verses. It didn’t take them long to craft the lyrics for the song, which was later finalized and included in the film:

"O German fascists, you are thieves,

You stole the field where we used to play.

Dance, Gëzimi! Keep going, Vaso, Tomka!

We are not afraid—this field is ours!

Our poor neighborhood, sunk in misery,

We only had this field to bring us joy as children.

Tomka, Çelua, I, and Vasua—we are four friends,

We love it, and it loves us—it is the pride of our street!"

This was the text those children created—simple, heartfelt, true to a child’s perspective, and perfectly aligned with the film’s message. For these children, who lived in the time of war, the Germans who had taken over their field were nothing less than thieves. I remember that the day we shot the scene, a wonderful energy filled the field, where, as always, nearly the entire town had gathered to watch.

ATHENS DESIGN FORUM: Can you recall special moments when Keko engaged with the community of Berat during the filming of Tomka and His Friends? How did her presence and approach influence the participation of local residents? What were the challenges and emotions during this process?

GENC PERMETI: Berat, with its unique architecture, has a link to Keko’s hometown in terms of the materials used, the influence of Ottoman structures, the narrow winding streets, the vertical rise above the mountain, and the relationships between the communities in both cities. For this reason, the author felt at home and comfortable in building relationships with the community of this city. The fact that some of the child actors were already well-known from previous films turned them into stars that the whole city wanted to meet. Families would invite them to stay in their homes overnight, which could be risky for the production and cause a disruption in discipline. On the other hand, this popularity worked to the advantage of providing extra actors and extras. One of the children (the youngest) was chosen by the kindergartens of Berat. The author promised the children of the city that she would hold auditions for small roles, a promise she had to keep. Another advantageous element was the city’s willingness to offer the best of their community by being very cooperative in helping with the production, which is often seen in small-town productions of the time.

The strongest emotion for the author was the film's premiere in Berat, where, as the author herself describes, "That evening, the whole city gathered in front of the cinema, wanting to enter to watch the film. I remember that the children reacted continuously during the film until... After the German camp explosion, the music that accompanied the lighting of the city’s lights was almost drowned out by the applause of the attendees. The entire theater stood up. It was a premiere that gave me an unparalleled joy.”

ATHENS DESIGN FORUM: Are there any spiritual or mythological narratives tied to the Osum River in Albanian folklore?

Genc Permeti, Ilir Keko: The Osum River—one of Albania’s most well-known rivers—flows through Berat and has played a crucial role in the city's development over centuries, giving rise to many fascinating legends. In Albanian folklore, rivers are often personified or associated with natural forces that reflect traditions, mythology, and the way of life of the people. One of the most famous legends concerns the river's name, which is believed to originate from a mythological event. Some versions suggest that "Osum" comes from an Illyrian word meaning "mighty" or "fast," referring to the river’s strength and speed. Others claim that the river was marked by ancient deities and has a deep connection to natural forces and the lives of those who have lived along its banks. Another legend tells of a time when the Osum River saved a group of people from disaster. According to this tale, a mysterious light appeared over the river, guiding the people to safety in a moment of great peril. This story carries mythological and folkloric elements, portraying the river as a powerful force that has shaped human destiny—often serving as a symbol of both uncertainty and the immense power of nature. A final legend links the river to strength and faith. Some traditions claim that the Osum has been an eternal lifeline, sustaining countless civilizations and communities. It has long been considered a source of life and progress, with many ancient traditions and religious rites performed along its banks—elevating it to a sacred status in certain aspects of local spiritual life. Overall, the Osum River is both a symbol of Albania’s untamed natural beauty and a vital element intertwined with the history and identity of the Albanian people.

<>

Genc Permeti is a Tirana-based producer, screenwriter, and visual artist. A graduate of the Academy of Art in Tirana (1989), he exhibited extensively across Europe before transitioning into film. From 2005 to 2014, he served as the main programmer of the Tirana International Film Festival. As founder of Ska-Ndal Productions (2006), he has produced acclaimed films such as Goran Paskaljević’s Honeymoons (2009), La Nave Dolce (Venice Critics’ Award, 2012), and Netflix’s Forgive Us Our Debts (2018). His latest production, Light Falls, directed by Phedon Papamichael, is in post-production. Permeti’s directorial debut, Leaving Eden (Mira), is set for a 2025 premiere. Ska-Ndal also champions Albanian cinema, notably distributing Xhanfise Keko’s films internationally in collaboration with institutions like the Danish Film Institute, BFI, and Lincoln Center.

Ilir Keko is an Albanian journalist and filmmaker with a career spanning nearly five decades. As a director at Albanian Radio Television for 40 years, he produced numerous documentaries and television programs, contributing significantly to the country’s media landscape. Son of esteemed filmmakers Xhanfise and Endri Keko, he now oversees their creative legacy, ensuring their work reaches new audiences. In collaboration with distributor Genc Përmeti, he actively promotes Albanian cinema internationally, preserving and sharing the rich heritage of his parents' groundbreaking films.

On “The Days of My Life” ~ Written in 2007, the final year of her life, “The Days of My Life” is the memoir of esteemed director Xhanfise Keko. This work provides a comprehensive account of her personal, familial, and artistic journey over the span of 79 years. In the artistic section, Keko chronicles her formative years studying film editing at the Documentary Film Studio in Moscow (1950–1952), followed by her tenure as an editor and montage director from the establishment of Kinostudio Shqipëria e Re in 1952 until 1970. “The Days of My Life” was posthumously published in 2008 by LILO Publishing House in Tirana, under the leadership of Adrian Laperi—one of the child actors in Beni Walks on His Own.

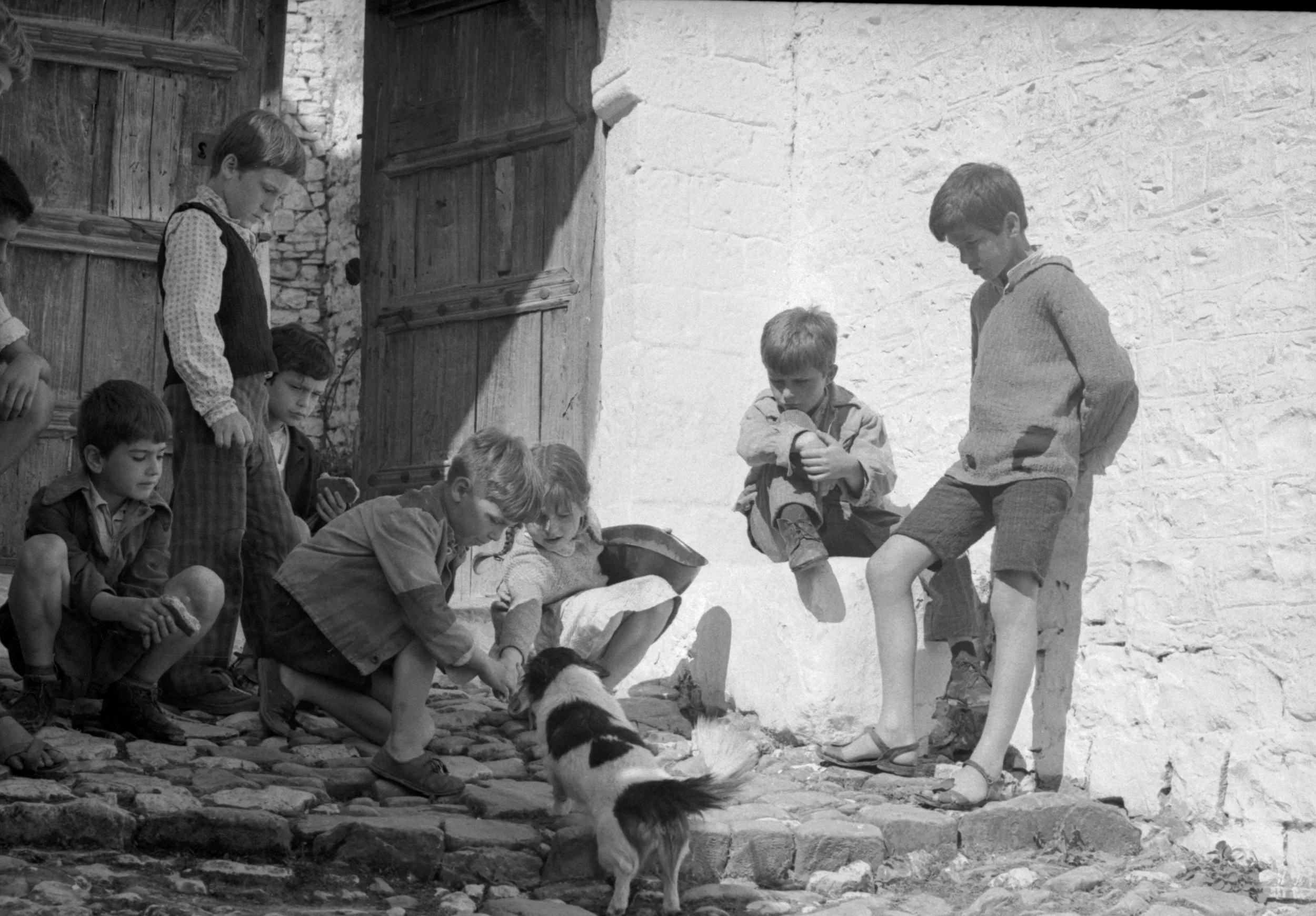

Film still of Tomka Dhe Shokët e Tij (1977) © The Albanian National Film Archive (AQSHF)

EVENT DETAILS

April 08, 2025 ~ 4:30 PM

Dropcity Center for Architecture and Design

Via Sammartini 38-60

20125 Milano, IT

Limited to 60 seats. A Q&A with Athens Design Forum’s Katerina Papanikolopoulos will follow.

Please arrive between 4:00-4:25.

Xhanfise Keko. Tomka dhe shokët e tij (Tomka and His Friends), Albania, 1977, b/w, original version in Albanian with English subtitles, DA, 72’

Filmmaker Biography ~ Xhanfise Keko

Kinostudio editor-turned-director Xhanfise Keko built a distinct and enduring filmography shaped by her experiences as a working woman in 1970s and 1980s communist Albania. Though once overlooked, her legacy persists through her pioneering focus on childhood, portraying children’s independence with a uniquely immersive approach. Her films employed a child’s-eye perspective, featuring non-professional actors and flexible scripts that allowed for authentic expressions.

Keko’s career began with formal studies in film editing at the Documentary Film Studio in Moscow (1950–1952), after which she worked as an editor and montage director at Kinostudio Shqipëria e Re from its establishment in 1952 until 1970. In 1964, she transitioned to directing documentaries, beginning with A Story About Working People, before dedicating herself fully to children's cinema in 1970. Between 1970 and 1984, she directed two children's documentaries incorporating artistic elements and 11 feature films for young audiences, cementing her influence on Albanian cinema. She retired from filmmaking due to health reasons.

Despite the constraints of strict censorship, Keko’s films remain culturally and historically significant. Her work has been rediscovered and celebrated internationally, with recent showcases at the Museo Reina Sofía (2021) and restoration efforts led by the Albanian Cinema Project (ACP). In 2014, ACP restored Tomka and His Friends (1977) in both 35mm and digital formats, introducing it to a global audience.

Keko was married to Endri Keko, Albania’s most distinguished documentary filmmaker. Together, they had two sons: Ilir Keko, a journalist of nearly five decades and a longtime director at Albanian Radio Television, where he produced numerous documentaries and television programs. He now manages his parents' creative rights and collaborates with distributor Genc Përmeti to promote their work internationally. Their second son, Teodor Keko, was a renowned journalist, poet, writer, and politician in Albania, who passed away in 2002.

Athens Design Forum ~ Film Programming

Founded by Katerina Papanikolopoulos in 2021, the non-profit Athens Design Forum (ADF) advocates for overlooked and generative design histories interwoven with global labor and migration patterns. Papanikolopoulos’ curatorial programming prioritizes photography and film as integral, critical methodologies to decipher design’s social role.

Since 2023, Athens Design Forum has introduced programming and special features with the following directors and collectives:

Juan Pablo González (Mexico) – Caballerango (2018), The Solitude of Memory (2014)

Hicham Gardaf (Morocco) – In Praise of Slowness (2023)

Izza Génini (Morocco) – Aïta (1988)

Yugantar Collective (India) – Tobacco Embers (1982), Sudesha (1983)

Mohamed Khan (Egypt) – El Batikha (The Watermelon, 1996)

Marta Rodríguez (Colombia) – Chircales (The Brickmakers, 1972)

Shasha Movies (Global)

Menelaos Karamaghiolis (Greece) – Gloria Olivae (1987)